Visit the Baseball History Comes Alive Home Page

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive

Free Bonus for Subscribing:

Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide

Relief Pitchers Photo Gallery

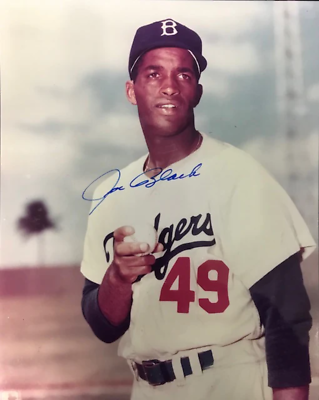

Today we welcome back Vince Jankoski with an interesting essay about the early evolution of the relief pitcher from Firpo Marbeerry in the 1920s to Jim Konstanty in the 1950. In the featured photo, we see the outstanding relief pitcher, Joe Black. –GL

THE EVOLUTION OF THE RELIEF PITCHER

Baseball evolves, slowly, ever so slowly, but it does evolve. Baseball’s gradual changes make it difficult to identify watershed moments in the game. There are a few truly breakthrough moments which can be isolated: the advent of the lively ball, night baseball, and breaking the color barrier. Even those historic changes to the game, however, came about gradually. Jackie Robinson’s shattering of the color line did not immediately usher in scores of black ballplayers into the major leagues. It took more than a decade for all teams to be integrated. It was the same for night baseball. Teams (especially the Cubs) were reluctant to install lighting and only grudgingly added a smattering of night games to their schedules. Most alterations of the game occur almost tortoise-like. Such is the case of relief pitchers.

In the beginning, there were no relief pitchers. There were just pitchers. Hurlers summoned to relieve their starting brethren were themselves starters, tasked to work between starts – a sort of athletic overtime. There were also the occasional mop-up men, pitchers not considered good enough to ever be starters, but when the game was on the line, a manager went with one of his starters to save the game.

As proof, in the Deadball Era, it was not uncommon for the league leader in saves to also lead the league in complete games. In 1903, for example, Cy Young led the American League in complete games (34) and saves (2). In 1908, Ed Walsh led the American League in both complete games (42) and saves (6). Over in the National League, Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown led the league in complete games and saves in both 1909 and 1910. In 1908, Brown, Mathewson, and Joe McGinnity tied for the National League lead in saves with five. Starters all, they would combine for 858 career wins and 1,050 complete games.

There were some minor aberrations. In 1911, Brown was used in relief nearly as much as a starter and set a major league record with 13 saves. Still, Brown had 27 starts that season. In the American League in 1913, Chief Bender tied Brown’s major league record for saves with more relief appearances than starts; however, Bender still recorded 21 starts that season.

Pitchers used solely in relief, to the extent that a team had any, were the Rodney Dangerfields of major league baseball. They got little respect. No one aspired to be a relief pitcher.

Then came Firpo Marberry, a Texan, who pitched for the Washington Senators from 1923-1932 and later with the Tigers and Giants. Firpo led or tied for the American League in saves six times. At the close of World War II, he was the all-time single-season save leader, a record he set in 1926. His 22 saves that season broke his own record of 16, which he set the year before, which, in turn, broke his own record of 15 set the year previous. However, even Firpo, whose real first name was Frederick, was used as a starter in about a third of the games in which he appeared. He even started Game Three in the 1924 World Series. Firpo’s career as a relief pitcher was an exception. He did not change the nature of the game insofar as relief pitchers go.

MLB went more than a decade before the next appearance of a true relief pitcher, Johnny Murphy of the Yankees. Murphy, who, after his playing days were past, became general manager of the New York Mets, started 20 games in his first full season in 1934, but went almost exclusively to the bullpen thereafter. Hitting his stride in 1938, he would lead the American League in saves in four of the next five seasons. In that span, he started only three games. He appeared in three All-Star games, but never finished higher than 33rd in the MVP voting.

Murphy went into the service in 1944. By the time he was mustered out, he was 37 years old and finished as a pitcher. His place in the Yankee bullpen was taken by Joe Page. Page was dominant in relief from 1947-1949. In that time period, he would amass 60 saves, starting only three times. He led the league with 17 saves in 1947 and 27 in 1949. He would finish fourth in the MVP voting in 1947 and third in 1949.

Notwithstanding Marberry, Murphy, and Page, in my opinion, the breakthrough guy, as far as relief pitchers go, was Jim Konstanty. In 1950, Konstanty, whose real first name was Casimir, played for the “Whiz Kids” Philadelphia Phillies. While not the oldest player on the roster, at 33 years old, he was no “Whiz Kid”. The previous season, he had modest success in 53 games, all in relief, going 9-5 with an ERA of 3.25.

Arguably, it was Konstanty’s 1950 season that changed relief pitching for good. That year, Konstanty went 16-7 with a league-leading 22 saves. He pitched to an ERA of 2.66 in 152 innings spread out over 74 games. He was third on his team in wins and fifth in innings pitched. The Phillies won their first pennant in 35 years. Konstanty was named MVP. Think about that. A guy at the position nobody wants to play is the Most Valuable Player. Relief pitching was never the same with all due respect to Marberry, Murphy, and Page.

After 1950, pitchers used solely in relief became more sought after and, indeed, respected: Johnny Sain, Joe Black, and later Luis Arroyo, Ryne Duren, Ron Perranoski, Mike Marshall, and still later a host of others. But it was Konstanty’s 1950 season that made it all happen. One could argue that it was one of the others and not Konstanty who would change perceptions, but I say winning an MVP and leading an also-ran to the pennant was what made the difference. Besides, Marberry pitched on good teams. Yes, the Washington Senators in the 1920s were a good team. Murphy and Page were stars on teams in the middle of the Yankee dynasty. Konstanty led a perennial loser to the pennant. He showed the value of a true relief pitcher.

The Phils won the pennant on the last day of the season, but lost to the Yankees in a sweep of the World Series. Konstanty had his only start of the year in the opening game. That, however, should not detract from his importance to future generations of relief pitchers. Konstanty’s 1950 season made relief pitchers what they are today. From obscure afterthoughts on pitching staffs to league MVPs, Konstanty made them all.

Vince Jankoski

We’d love to hear what you think about this or any other related baseball history topic…please leave comments below.

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive. FREE BONUS for subscribing: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide. https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Information: Excerpts edited from