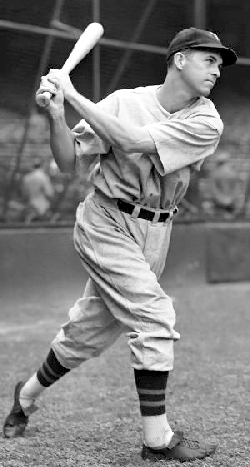

The Case for Inducting Cecil Travis into the Hall of Fame

Introduction

Before long, the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Classic Era Committee will convene to consider voting for worthy candidates for enshrinement who played in the major leagues before 1980. Taking nothing away from his “competitors,” we respectfully submit that Cecil H. Travis is the most deserving among all eligible former ballplayers who fit that description. In fact, it’s difficult to understand how he managed to escape the Hall’s serious attention for so long, considering his outstanding record, his inspiring character and heroic service during WWII, and the fact that he has been retired from the game, i.e., available for election, for more than 75 years. We strongly urge the committee to correct this unwitting injustice now, before Cecil Travis’s sterling life and career fade totally from the voters’ collective memory.

Criteria for Enshrinement

As members of the Classic Era Committee surely know, here are the prevailing standards upon which all eligible candidates should be considered for induction into the Hall: record, ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contribution to one’s team. We strongly believe, and intend to show, that Mr. Travis meets, and actually exceeds, all of the expectations rightly placed upon potential Hall-of-Famers before they’re allowed to take up permanent residence in Cooperstown.

The Record

Cecil Travis, born in the late summer of 1913, launched his professional career as a teenager when he joined the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern League in 1931, hitting a phenomenal .429 in thirteen games. He stayed with the team, a Double-A affiliate of the Washington Senators, in ’32 and ’33, chalking up season averages of .356 and .352 before being called by Washington to the major leagues at the age of 20, in 1934. He promptly ran off a string of seven seasons over the next eight years in which he batted well over .300, described in more detail in the paragraph below. But in the spring of 1933, when asked by the parent club to spell Ossie Bluege, the Senators’ injured third baseman, a 19-year-old Travis racked up five hits in the very first major-league game he ever witnessed — a feat not duplicated by any of the thousands of ballplayers who appeared on the big stage in the 90 years since.

Although he would be installed at shortstop in 1937 and for the rest of his career, by 1934 this 20-year-old model of consistency was anchoring the “hot corner” for Washington on a regular basis. Save for 1939, when he suffered several bouts of influenza which drove him from the field for extended periods, dragging his average down to a career-low .292, he would bat .319, .318, .317, .344, .335 and .322 heading into 1941, a storied season in which Joe DiMaggio hit safely in a record 56 consecutive games, and Ted Williams became the last big-leaguer ever to bat .400. Travis, by then a three-time All Star, hit an astounding .359 that year, second only to Williams in the major leagues. His 218 hits set a single-season record for shortstops that would endure for nearly 60 years, until Hall-of-Famer Derek Jeter managed 219 safeties in the materially longer season of 1999. That giant number by Travis topped DiMaggio’s total by 25, and Williams’s by a ridiculous 33, despite a watershed year for which those two icons will forever be honored and remembered.

.

For a middle infielder without the long-ball in his arsenal (only 7), his OPS (on-base-plus-slugging) average of .932 opened the eyes of competitors: Williams declared Travis “one of the five best left-handed hitters I ever saw.” Bob Feller’s published list of his all-time toughest outs featured Williams and DiMaggio, Jimmy Foxx, Hank Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, and a natural-born hitting phenom who had the misfortune to toil in relative obscurity throughout his career as a member of a chronically second-division ballclub. When the halcyon season of 1941 ended, Travis, who turned 28 the month before, was recognized by The Sporting News as the best shortstop in the game. His stats for the year included 39 doubles, 19 triples, 316 total bases, 106 runs scored and 101 driven in. His lifetime batting average was by then a single point beneath Honus Wagner’s .328, then and to this day the highest of all shortstops, living or dead. For his relatively short, eight-year career, Travis had already accumulated 606 runs, nearly 600 RBI (581), and 1,370 base-hits. At that rate, without even factoring in his impressive trajectory as he approached his prime, Travis would easily collect more than 3,000 hits and a likely lifetime batting average of .330, if not better.

The War

But in late 1941, Imperial Japan’s bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, sending the United States into WWII. Promptly joining the military, Cecil Travis willingly surrendered the next four seasons, and the height of his anticipated dominance as a major leaguer, to the cause of liberty, ages 28-29-30 and 31. When the war finally ended, in September of 1945, he was already 32 years old.

Advancing years, in and of themselves, might have slowed Travis down a bit in the post-war, but thanks to serious wounds which essentially finished his athletic career altogether, we can only guess about that. In the winter of 1945, as a member of the Army’s 76th Infantry Division, he devoted two long and excruciating months to The Battle of the Bulge, the deadliest of all engagements faced by this country in the entire war. Hitler’s army hit the Ardennes Forest with 200,000 troops and a thousand tanks on a mad but ill-fated drive to the English Channel. Awarded the Bronze Star and no fewer than four (4) battle stars for his courageous service under fire, Travis was obliged to undergo special surgery in order to salvage his frozen feet from likely amputation.

Unlike returning baseball heroes such as Bob Feller, Ted Williams, Warren Spahn and Gil Hodges, WWII brought an end to Travis’s days of glory and accomplishment on the playing-field. He never said so, but permanent damage to the tissue and ligaments in his frost-bitten feet had reduced his speed afield, and ruined his balance at the plate. He tried gamely for a comeback in 1946, managing to appear in 137 games while batting more than 100 points below his ’41 average (.252). Just 74 games into the following season, hitting an uncharacteristically dismal .216, Travis chose to retire. The hitting machine with the eye of an eagle had become an easy out.

.

We can never know exactly what the uninterrupted baseball career of Cecil Travis would have looked like, but this much is sure: On “a date that will live in infamy” he was a .327 lifetime hitter, with eight full seasons of major-league baseball under his belt. By the summer of 1949, at age 35, he would already be nearing the end of his sixteenth season. In our opinion, the committee need not speculate excessively by projecting that Travis would still be going strong at that point, a ballplayer in his mid-30s with more than 3,000 hits to his credit already, and a batting average in the neighborhood of .330. As it was, his war wounds caused a once-stratospheric average to plunge, and he wound up retiring at .314, a number still higher than 22 of the 24 shortstops in the Hall of Fame, and the highest of all shortstops who ever played in the American League.

Ability

As mentioned, Cecil Travis was a hitting machine. Sporting an average of nearly.360 over two-plus years in Double-A ball as a teenager, and batting safely an all-time record five times in his big-league debut, at age 19, he simply went on hitting, consistently and for high average, throughout his tragically blunted career. Small wonder that a hitter no less accomplished than Ted Williams himself called Travis one of the best, and that Bob Feller considered him among the toughest hitters of all.

Integrity

Cecil Travis was a shining example of what Tom Brokaw once named “The Greatest Generation.” He dedicated four years of his life to the cause of liberty, including the very prime of an otherwise magnificent athletic career. When asked to comment upon having been deprived (temporarily) of membership in the Hall of Fame as a result, Travis said simply, “Baseball is just a game. We had a job to do, an obligation, and we did it. I was hardly the only one.”

Sportsmanship

Unlike many more-colorful and combative players and self-promoters, the understated Travis politely declined his superiors’ demands that he retaliate in kind whenever spiked, body-blocked or beaned by the opposition. The major-league umpires of the time voted him their favorite participant in the game.

Character

A war-hero with five (5) awards to his credit for courage under fire and no plaque in Cooperstown (yet), Cecil Travis forever refused to blame the war for having derailed a nearly-certain Hall-of-Fame career. He didn’t complain about the cruel hand dealt to him, and he never asked to be considered for enshrinement. Near the end of his last season, Travis was honored by a “night” at Griffith Stadium, and Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in the European Theater of Operation where this intrepid ballplayer/soldier had served with such distinction not long before, attended the ceremonies to voice his appreciation.

Contributions to the Team

Travis was clearly the best player on the Washington Senators for the (pre-war) life of his big-league career, 1934-41. Manager Bucky Harris said so, and his teammates agreed.

Conclusion

Cecil Travis was en route to the Hall of Fame when a cause greater than our National Pastime intervened. He immediately recognized which had priority and responded accordingly, sacrificing his playing days for the cause of liberty. Rather than penalize him any further for answering the call in our nation’s time of greatest need and putting his life on the line, we urge the Classic Era Committee to follow the lead of one (1) Dwight David Eisenhower, and recognize this man for the remarkable specimen he was – and is.

Michael H. Keedy