Panoramic Photo Above:

Shibe Park , Philadelphia

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions From Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Visit the Baseball History Comes Alive Home Page

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive

Free Bonus for Subscribing:

Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide

C’mon now…be honest! How many of you are aware that one of the original 1876 teams in the National League was the Hartford Dark Blues? That’s what I thought! Today Ron Christensen gives us a little refresher history lesson about the early days of the National League and the role played by the Hartford Dark Blues. Since we always look for ways to enhance our knowledge of baseball’s early days, I found Ron’s essay enlightening – and I think you will too. I hope you’ll take a couple minutes to read Ron’s interesting essay. –GL

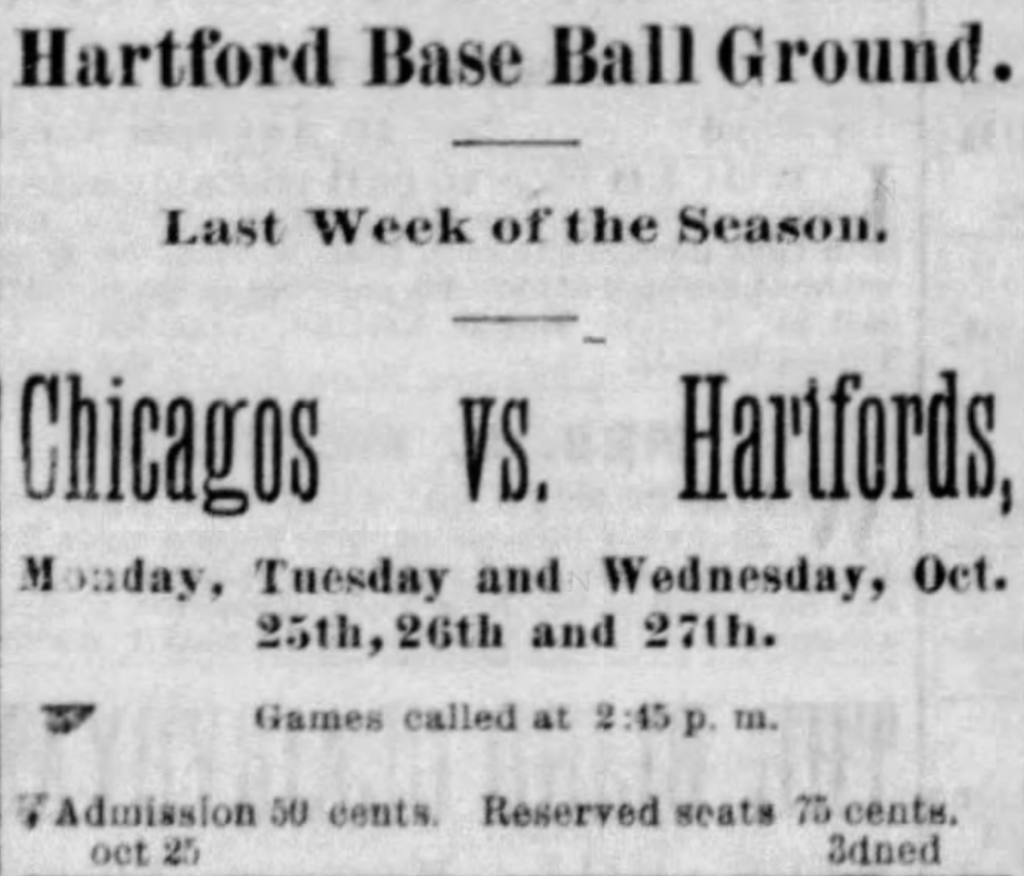

SELLING OUT THE HARTFORD DARK BLUES!

In the mid 1870’s, Hartford was the biggest little city in baseball. Not amateur baseball. Not industrial league baseball. Major League baseball! At a time when the inaugural National League required that member teams come from cities with populations of 75,000 or more, Hartford fielded a National League team despite having a population of only 37,000. But then, Hartford always did punch above its weight.

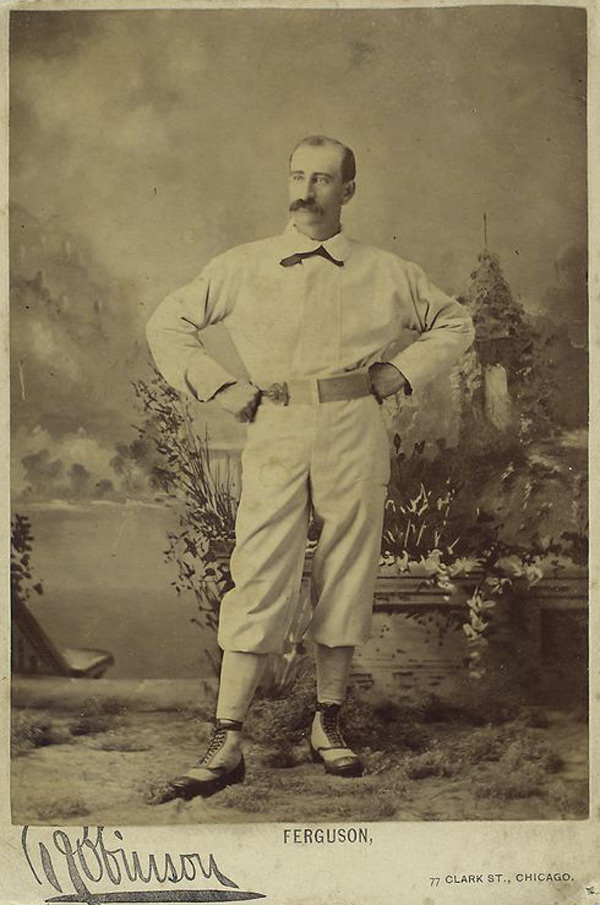

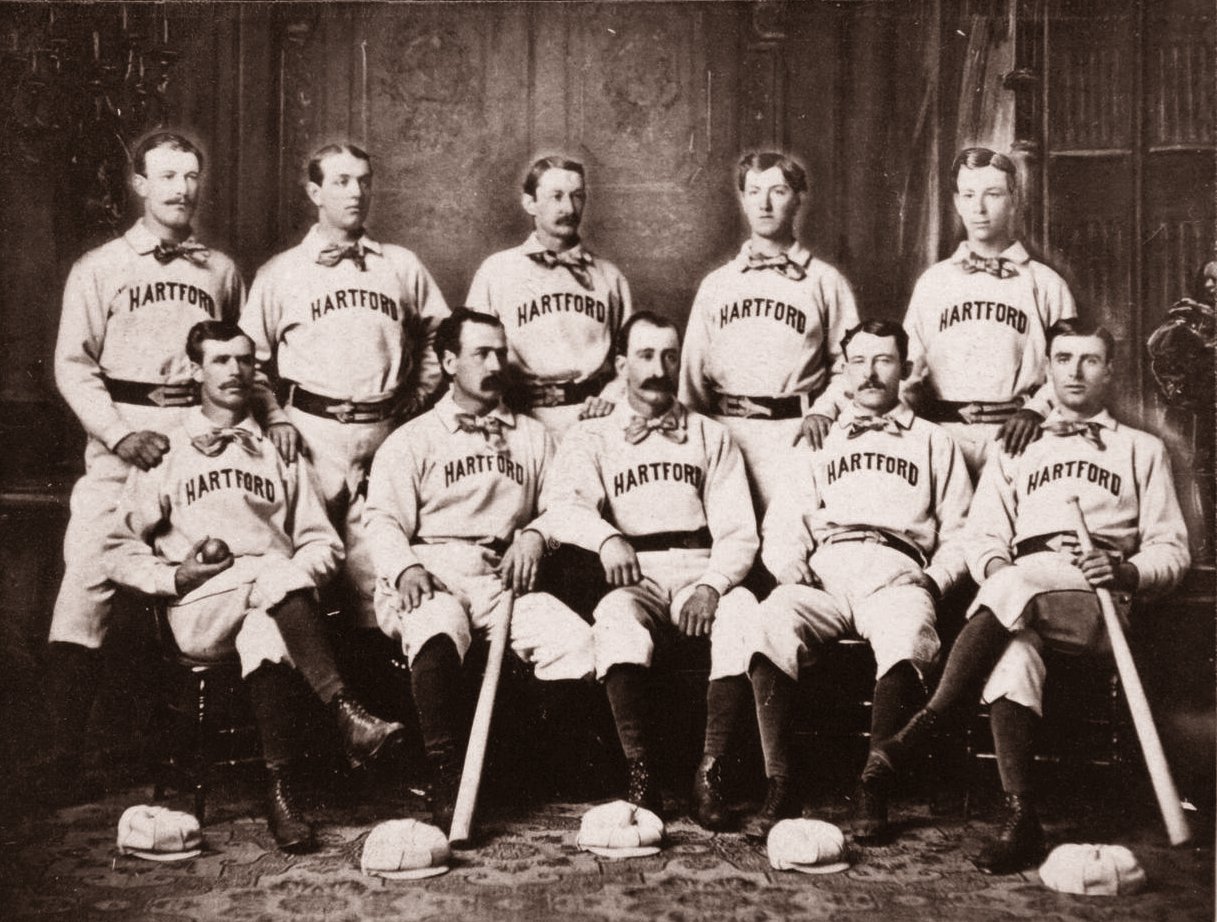

(Featured photo of the Hartford Dark Blues: L to R, Standing: Jack Remsen, Tom York, Candy Cummings (HOF), Tommy Bond and Bill Harbridge. Seated: Doug Allison, Everett Mills, Bob Ferguson, Tom Carey and Jack Burdock.)

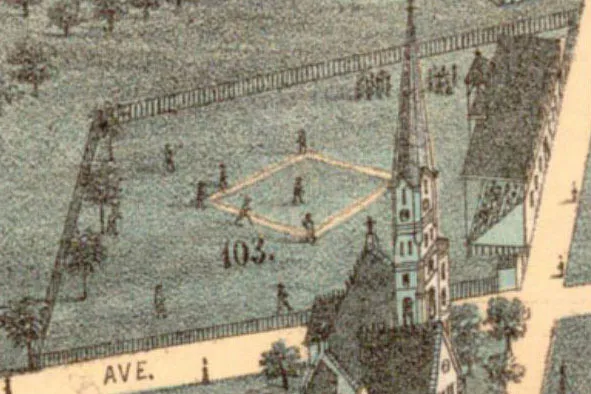

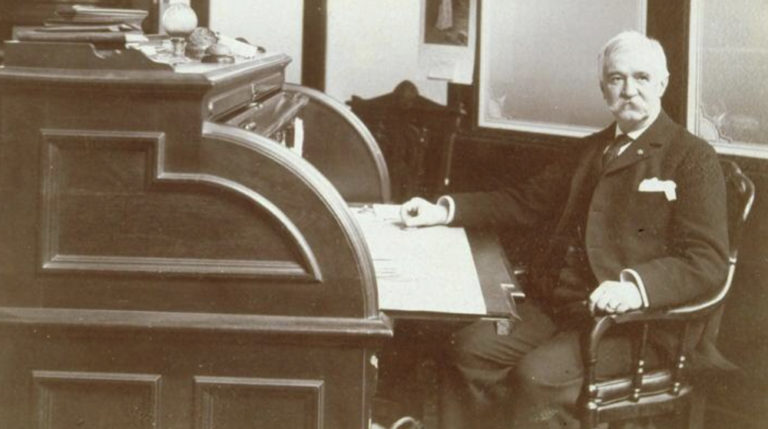

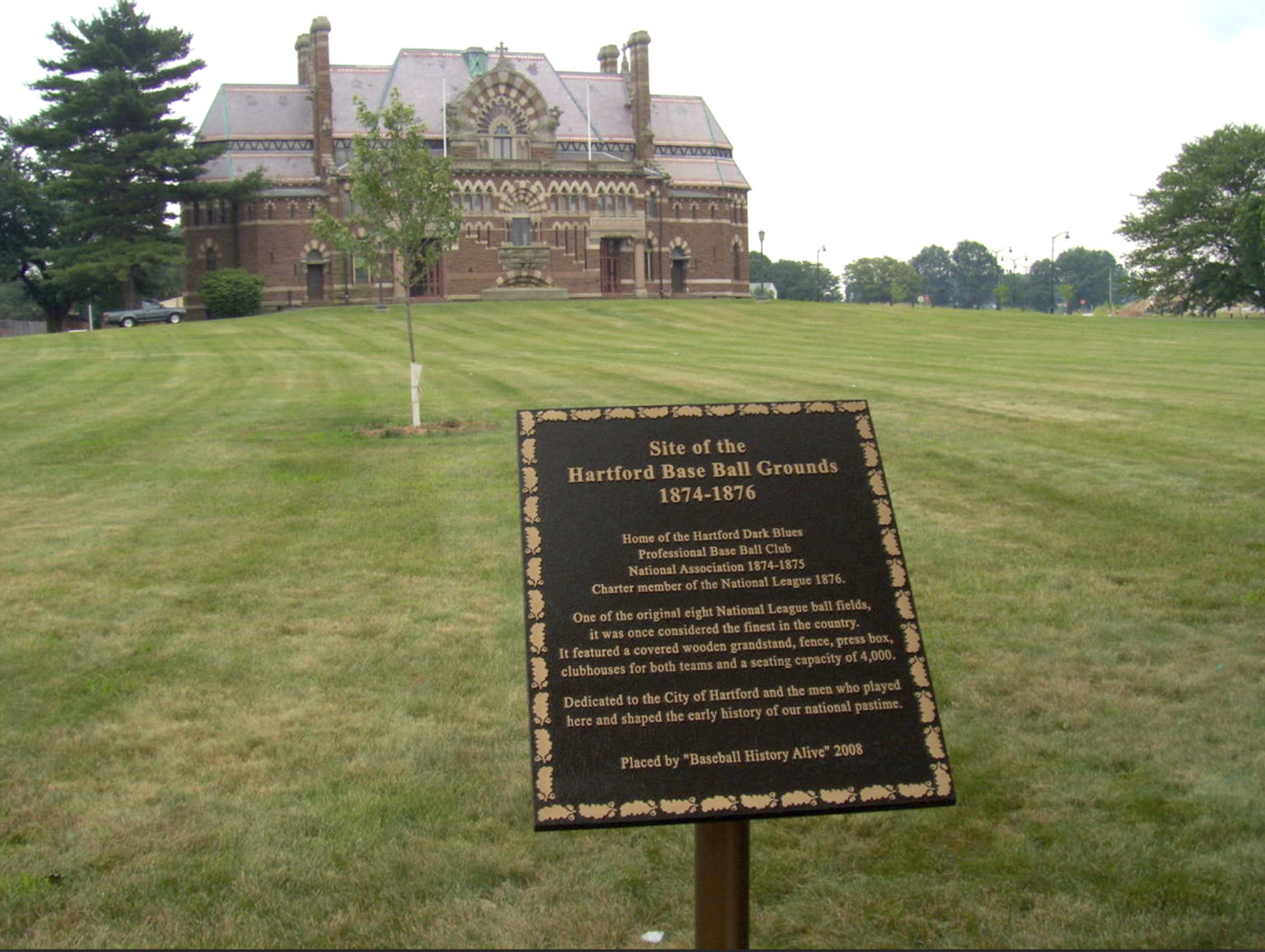

Hartford’s team was the Dark Blues, so named for the color of the stockings worn by its players. The team had a state-of-the-art ball field that was the envy of the rest of the league, built in a meadow that was leased from Elizabeth Colt, widow of Samuel Colt of Colt Revolver fame. Mark Twain, who lived nearby, was an avid fan and supporter. The team’s president and major investor was Morgan Bulkeley, a well-respected Hartford businessman with a reputation for strong leadership. Bulkeley, a Civil War veteran and future governor of Connecticut, was the head of the Aetna Insurance Company, a company founded by his father.

Hartford’s first foray into professional baseball was in 1874 with the National Association, founded three years earlier as the first professional baseball league. The team’s presence in the league was short-lived, as the National Association would fold after the 1875 season. Through the vision and effort of William Hulbert, owner of the Chicago White Stockings, the National League was founded and opened with eight member teams in 1876. Morgan Bulkeley was named league president.

Despite the strong showing of the Dark Blues that inaugural season, trouble was brewing in Hartford. A depressed economy had reduced gate attendance from 40,000 in 1875 to 18,000 in 1876. Though this was true for all teams that season, in a smaller city such as Hartford, with less people to draw from, the impact on team coffers was more pronounced. As the Depression continued, so did the teams financial woes, a reality not lost on businessman Morgan Bulkeley, who as the club’s primary investor was required to dip into his own pockets to aid his team’s bottom line.

Over in Brooklyn, a plot was being conceived by William Cammeyer, president of the Brooklyn Mutuals, and manager of the Union Grounds where the Mutuals played their home games. The Mutuals were Brooklyn’s entry in the National League. Like every other team that first season, the Mutuals felt the impact of the Depression. But more than that, Brooklyn had become a haven for washed-up and discipline-poor players that other teams didn’t want, which led to disinterest among the Brooklyn fan base. It wasn’t just the Depression that negatively impacted gate receipts, it was also the fans turning their backs on the team.

Toward the end of the 1876 season, Cammeyer announced that the Mutuals would be unable to make their final western road trip, something specifically forbidden by league rules and a violation that mandated league expulsion. Thinking ahead, Cammeyer approached Bulkeley, and the two discussed the possibility of moving the Dark Blues to Brooklyn.

From a business standpoint, the move made sense. The Dark Blues were losing money in Hartford, and this was likely to be compounded by a proposed new rule beginning in 1877 that visiting teams receive a stipend of 15 cents for each person attending the game. Hartford had a number of shareholders and season ticket holders who purchased their tickets in advance at greatly reduced rates, allowing them to attend individual games without paying as they entered. Their attendance would now be included in determining the visiting team’s portion of the gate receipts, a further crimp on the financial concerns Bulkeley envisioned moving forward. The same was not true in Brooklyn, where everyone who entered Union Grounds paid cash to attend games.

Also in Cammeyer’s plot was the possibility of reviving the interest of the Brooklyn fan base. It was widely recognized that the Dark Blues were the most disciplined team in the league, as well as the team with the best defense. They were a fun team to watch, and for the past two years had found themselves in a pennant race for the championship, something that always garnered fan support. Allowing the Mutuals to be expelled from the league, then replacing them with the Dark Blues, was looking more and more like a win-win for both owners.

Hulbert didn’t want to expel Brooklyn after only one season, knowing this might create some backlash for his upstart league. He offered to help finance Brooklyn’s final road trip as an incentive to avoid expulsion, and Cammeyer politely refused. When the season ended the writing was on the wall – the Brooklyn Mutuals weren’t returning for the 1877 season.

During the offseason, Bulkeley renewed his players’ contracts, stipulating himself rather than the ‘Hartford Base Ball Club’ as the contracting party. Buckeley also resigned his position as National League President, paving the way for Hulbert to replace him. Hulbert now saw the move of the Dark Blues to Brooklyn as potentially stabilizing for the league as a whole, and joined the negotiations in an effort to help finalize a deal. One incentive he engineered was the reduction of the visiting team’s gate receipts from fifteen cents to twelve and a half cents per ticket sold – but only for Brooklyn, something he strong armed the other clubs to endorse.

Though my reference here is eighty or ninety years premature, ‘the fat lady sang!’ Hartford was moving to Brooklyn. Brooklyn fans now had a new and better team to root for. Cammeyer had a new and viable tenant for his Union Grounds property. Bulkeley could now stem the financial bleeding that was forecast for the team in Hartford. Hulbert had now strengthened the financial posture of his upstart league. Everyone won, except the Hartford fans, who were now forced to seek other distractions to help mend their broken hearts.

All that was left to do was settle on a new name for the team. After much discussion, it was agreed to call the team the Brooklyn Hartfords, though I’m sure the Hartford fans would have preferred the Brooklyn Traitors or the Brooklyn Benedict Arnolds. The move to Brooklyn would be the first time in baseball history that a team changed cities without changing ownership. As we all know, it would not be the last. It would happen again, 80 years later, and it would happen in Brooklyn.

Ron Christensen

REFERENCES:

- National Baseball Hall of Fame, Morgan Bulkeley

- Wikipedia: Morgan Bulkeley

- Wikipedia: Hartford Dark Blues

- Major League Baseball in Gilded Age Connecticut, by David Arcidiacono

- Grace, Grit and Growling – The Hartford Dark Blues Base Ball Club, 1874-1877, by David Arcidiacono

Much of what I’ve written is sourced from David Arcidiacono’s two exceptional books, Major League Baseball in Gilded Age Connecticut, and Grace, Grit and Growling: The Hartford Dark Blues Base Ball Club, 1874-1877. His books were not only invaluable in piecing together this short essay, but are fascinating reads for anyone interested in vintage baseball, especially vintage baseball in Connecticut during the nineteenth century.

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive. FREE BONUS for subscribing: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide. https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Love the essay. The 1874 season included Al Spalding winning every one of the Boston Red Stocking victories and over 600 innings pitched.

I love the history of small cities histories in late 18th century baseball. Worcester had John Lee Richmond throwing the first perfect game in history.

And who can forget Hoss Radbourne and his historic season with the Providence Greys in 1884.

Phenomenal Smith “discovered” Christy Mathewson pitching for a minor league team in Taunton, Mass.

Thanks Paul…great points. I had a feeling you’d like this one!

Thank you Paul. Very glad you enjoyed the essay. Like you, I too enjoy the history of pre-1900 baseball, and there is so much of it that took place here in New England. I’m very familiar with Lee Richmond’s perfect game, and Hoss Radbourn’s achievements in 1884. But I must admit, I was unaware that Christy Mathewson pitched in Taunton. You sure know your stuff! Thanks again for your very nice comment.

Yes. New England played an important role in the early days of the game. (Although the New York rules beat out the Massachusetts rules).

I live two towns over from the birthplace of one of the founding fathers of the game, Doc Adams, who was born in Mont Vernon, NH.

I believe his contributions to the development of the game deserve a place in the HOF; just as deserving, if not more so,as Alexander Cartwright.

Cartwright gets credit for some of the rules developed in the early game that really were written by Adams.

Now if we can just Paul Doyle to write another essay…Doc Adams??

I second that!!

Gary – amazing job with the old photos! Yes, the “House of Good Shepherd” Church is still there. It was erected by Elizabeth Colt in memory of her son and husband who had both predeceased her. I don’t know how you do it, but you absolutely do an incredible job with the vintage photos you add to the essays. I truly believe they make my essays better and more readable than they are!

Sure thing Ron…glad to do it! And thanks for your contributions!