Featured Photo Above:

1924 World Series, Giants vs. Senators

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Visit the Baseball History Comes Alive Home Page

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive

Free Bonus for Subscribing:

Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide

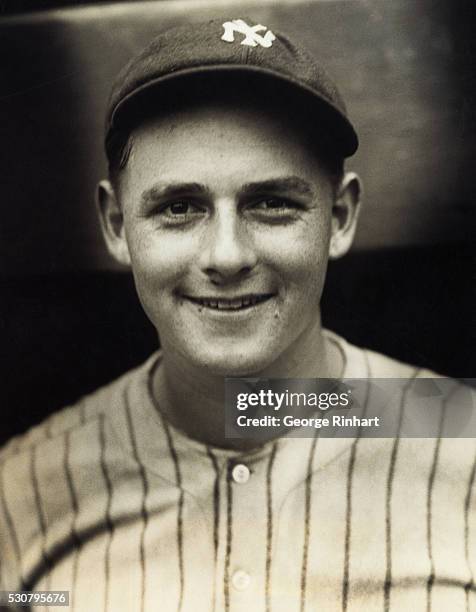

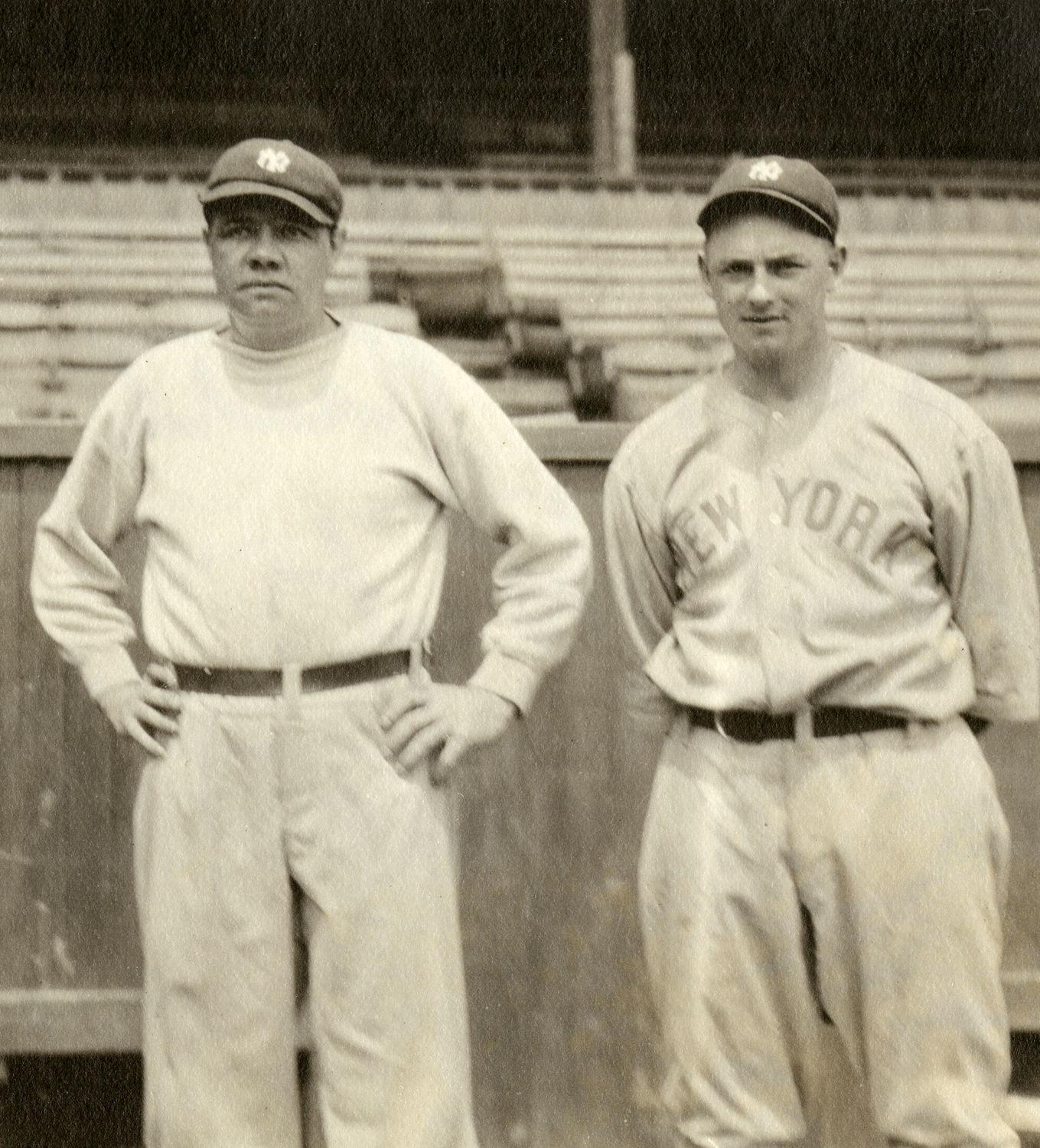

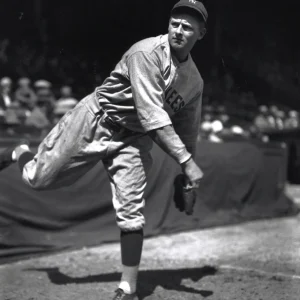

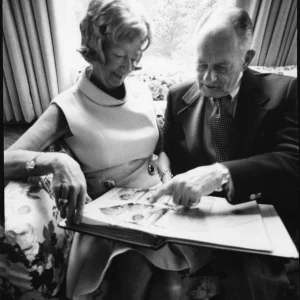

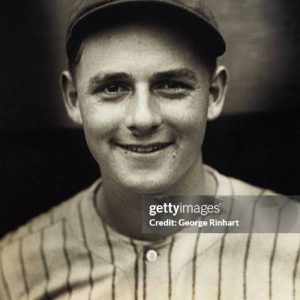

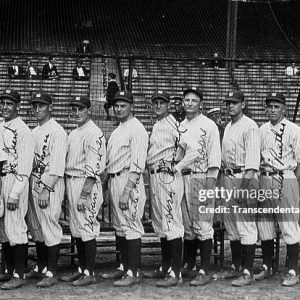

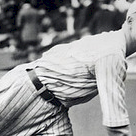

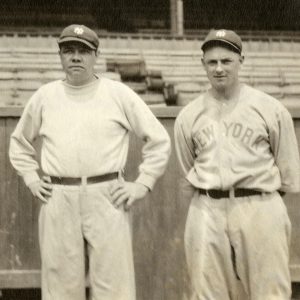

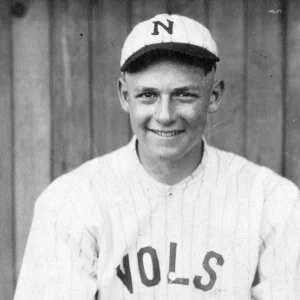

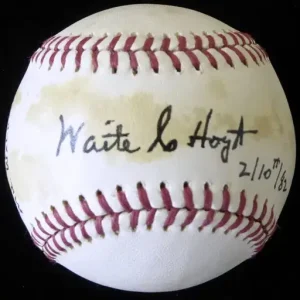

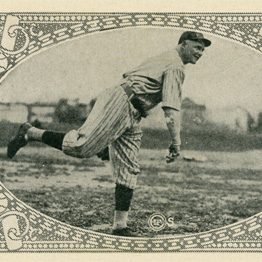

Waite Hoyt Photo Gallery

Amidst all the “heavy” writing we do around here on Baseball History Comes Alive, it’s fun to sit back every once in a while and have a good laugh. I guarantee that will be your reaction when you read Ron Christensen’s essay today about Waite Hoyt and the Dead Body in the Trunk. As far as I know, Waite joins with Andre Dawson as the only two ball players who were also morticians, although Waite joined the profession while still an active player, whereas Andre bought his funeral home in Florida after he retired from the game. (Click on this link to read about Andre’s unusual post-baseball career.) Anyway, read Ron’s essay and have a good laugh! -GL

Another Edition of:

From the Lighter Side!

Waite Hoyt and the Dead Body in the Trunk!

You never really know baseball until you put on a pair of cleats and get out and play it, and if you play for five years, you still don’t really know what it’s about. –Waite Hoyt

Waite Hoyt was the best pitcher on arguably the greatest baseball team ever to take the field – the 1927 New York Yankees. Alongside the ‘Murderers Row’ fueled offense, Hoyt led an accomplished pitching staff in wins, games started, complete games, and innings pitched. His 22 wins tied him for the American League lead, and his .759 winning percentage was league best. Over his career, the well-travelled Hoyt place for nine teams and posted a 237-182 record (.566), with a 3.59 ERA, 26 shutouts, and 226 complete games. He was a key contributor to three Yankees World Series championships (1923, ’27, and ’28) and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1969. (1)

Waite Hoyt’s Unusual Profession: “The Merry Mortician!”

Waite Hoyt was also a mortician. His father-in-law at the time owned a funeral parlor in New Rochelle, and Hoyt apprenticed with him to learn the business, believing that one day his wife would inherit it. As a result, Hoyt was branded with the nickname ‘The Merry Mortician,’ and the name stuck. (2)

Among his more interesting duties were his trips to the Manhattan morgue to retrieve bodies for delivery to the funeral parlor in New Rochelle. Hoyt would do this in the morning before ballgames, and while in Manhattan, would stop for breakfast at his favorite local eatery, Wing Sing’s Tea Parlor on Doyers Street in Chinatown, which was close to the Manhattan Morgue. Hoyt would refer to these runs as his ‘Breakfast and Body errands.’

On one such errand, Hoyt took teammate Myles Thomas with him. Arriving in Manhattan, the two stopped first at Wing Sing’s for a breakfast of dim sum, then headed to City Hall and to the morgue to sign out the body.

Waite Hoyt’s Unusual Cargo!

After a brief wait, two attendants came out with a body sealed in a body bag being wheeled on a gurney. The attendants helped move the body to Hoyt’s vehicle, placing the body in the backseat. Hoyt noticed the time and realized there was no way they could drive the body back to New Rochelle and return to the Bronx in time for the game. Believing their only viable option to be to drive directly to the Stadium, Hoyt decided to do just that. He told Thomas that when they arrived, he would call his father-in-law and tell him to come and pick up the body. Thomas, liking the idea less and less, was assured by Hoyt that all would be fine and that he had done this before on other occasions. But first, the two had to move the body from the backseat to the trunk so that the body wouldn’t be visible inside Hoyt’s car in the Stadium parking lot while waiting to be picked up.

The Game Infringes On Waite’s Professional “Duties!”

When they arrived at the Stadium, there were no shaded areas to park in, and the day was proving to be a scorcher. Hoyt told Thomas that even in the sun, the body would keep for an extra hour or so until his father-in-law could arrive to take it. As the two entered the stadium, they were met by team trainer, Doc Woods, who told Hoyt that Miller Huggins was looking for him and wanted to see him right away. Hoyt postponed the call to his father-in-law in favor of seeing Huggins in his office. When Hoyt entered, Huggins proceeded to tell him that he was pitching today, something Hoyt wasn’t expecting because he pitched in relief the day before. Now Hoyt’s mind became preoccupied with preparing for the game he had to pitch against the Red Sox, and of course, he forgot to call his father-in-law about the body temporarily entombed in the trunk of his car in the parking lot of Yankee Stadium.

The game moved along well for the first three innings. Hoyt was cruising, almost untouchable, surrendering no hits, no walks, and allowing only two weak fly balls to left field. Then, in the fourth inning, everything changed. Hoyt appeared to lose his composure. He paced around the mound, kicking up dirt. He walked the first batter on four pitches, gave up two quick singles, and before an out was recorded, the Sox scored two runs. All the while, players inside the dugout could hear Hoyt continually repeating the word “Goddammit!, Goddammit!, Goddammit!” Hoyt had finally remembered he hadn’t called his father-in-law about the body in the trunk.

All’s Well That Ends Well…I Guess!

Huggins sent Bob Shawkey to the mound to try and calm down Hoyt, and when he got there, Hoyt told him about the dead body in the trunk of his car and told him to return to the bench and tell Thomas to get some ice to cover the body with. Shawkey laughed, obviously not anticipating this circumstance when he walked to the mound. He returned to the dugout and relayed the message to Thomas, who, with the help of Doc Woods and two of the ballboys, put twenty pounds of ice into the trunk of Hoyt’s car. When the inning finally ended and Hoyt returned to the dugout, Thomas confirmed that the ice was in place and that, at least for the moment, all was well. “I just hope this doesn’t go extra innings!” he said to Hoyt. (3)

As soon as the game ended, Hoyt jumped in his car and drove the body back to New Rochelle. This may well be the first and only time a dead body has attended a baseball game at Yankee Stadium.

Ron Christensen

We’d love to hear what you think about this or any other related baseball history topic…please leave comments below.

CITATIONS:

- Baseball Reference

- Schoolboy – The Untold Story of a Yankees Hero, by Waite Hoyt with Tim Manners

- Hoyt the Mortician, by Myles Thomas, 2016

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive. FREE BONUS for subscribing: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide.

Good story. I suppose where Hoyt pitched for nine teams, some of them considered him

“dead weight”. As a mortician, he probably knew best how to field a “suicide squeeze”.

Seriously, Hoyt also had a Hall of Fame broadcasting career calling Reds games for 24 seasons, including the ‘61 Series.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=TaB0coqadHE

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=TaB0coqadHE

Clever, Paul…clever!

A fun story, but it’s important to note that this essay is based on a fictional account of a true event (the Diary of Myles Thomas, written by Douglas Alden). Waite Hoyt was a mortician and did leave a body cooling in his trunk while he pitched an afternoon game at Yankee Stadium, but most of the rest of these details are not true. BTW, Hoyt hated being called “The Merry Mortician.” 🙂

You’re confirming that he was a mortician, and that he “did leave a body cooling in his trunk while he pitched an afternoon game at Yankee Stadium.” So what parts of the story are “not true”? (your words).

Other than the stats at the beginning of the essay, pretty much the rest of it. This is how Hoyt told the story in “Schoolboy: The Untold Journey of a Yankees Hero,” his memoir:

“That summer, there was a death in Larchmont and Hoyt & Meehan was called on to prepare the remains for transportation, provide a casket and so forth. Where do you think the burial was to take place? In Brooklyn! And my father-in-law was to handle the internment.

The remains and the casket had to be transported in a vehicle with a canvas cover that buttoned down over the trunk. Dick Meehan said to me, “You know, I’ve got to get this body over to Brooklyn, but I don’t like to leave the place alone.” Well, the Yankees were playing at home, so I told him I could take care of it for him.

I’m not making a joke out of this because there is some respect to be shown to the gentleman, but the funny thing is I was pitching that day. So, I drove the vehicle down to Yankee Stadium and parked it in the lot. I pitched the game and then drove the body over to Brooklyn. I imagine that was the first and last time anything like that ever happened at Yankee Stadium. “

Thanks for your input Tim.

To be fair, it’s not just the stats that are accurate. Hoyt was a mortician. He apprenticed with his father in law and initially thought he might one day run the business if his wife inherited it (which of course didn’t work out – the wife or the business). He did make vehicle runs to pick up and deliver bodies, and he did leave a deceased body cooling in the trunk of his vehicle one summer afternoon when he parked it in the Yankee Stadium lot, stopping first to pitch a game before delivering it for interment.

These basic elements of my essay are factual and accurate. The added “color commentary” comes from the ESPN project “The Diary of Myles Thomas”, and though quite plausible, is fictional. The recitation you cite from your book comes directly from Hoyt, and therefore is factual, though when I read it, it did seem to me to be fairly light on details. Given the circumstances of arriving at a ballpark to pitch a game with a dead body in tow begged the question of wanting more. It’s an incredibly unusual circumstance, and Hoyt deals with it almost casually. Candidly, the Myles Thomas version, though embellished, seems more fitting to the circumstances and is arguably the more interesting version of the story even if not the more accurate one. I just had the feeling when reading this chapter that there was more to the tale than Hoyt was telling. I’m curious to know if you had that feeling as well when you were writing it.

Please know that my comments are not meant to criticize. You presented an accurate, factual version based on Hoyt’s own comments, and did so in highly readable fashion. Possibly because I was hoping for more detail I was drawn to the ESPN version, and ran with it to formulate an essay that I thought might be more enjoyable to readers. And while I freely admit to basing the essay on the Myles Thomas version of the story, and acknowledging that this version is embellished with fictional details, I do believe that what I’ve written offers more factual information than just Hoyts seasonal and career stats, though we may ‘agree to disagree’ on this point. In the end, I hope readers will enjoy reading the essay – both for its place in baseball history as well as for its entertainment value.

Thank you, Tim. I’m grateful and flattered to have your feedback. I want to congratulate you on your book, which I’ve read twice now (some chapters more than twice), and which I’ve enjoyed very much. I also enjoyed your online interview with Chris Russo, so consider me a fan. Shamelessly, if I ever do have the pleasure to meet you in person, I will ask you to autograph my copy of your book.

To further clarify, “The Diary of Myles Thomas” was an ESPN project created by Douglas Alden and presented in real time across ESPN’s social media platforms throughout the 2016 baseball season, but done as an exploration of the 1927 New York Yankees season amidst the backdrop of the Roaring 20’s, Prohibition, the Jazz Age, and what it was like to be an athlete on the greatest team of all time – all as seen through the eyes of Myles Thomas, who was in fact a very real member of the ’27 Yankees.

Yes, it is historical fiction, though all based on true events. As you know, Alden brought in John Thorn to assist with the project – Thorn being Major League Baseball’s Official Historian. Thorn’s role was to assure readers that what was written never veered too far from known fact, and that it never contradicted known fact. As a historian, Thorn said it was his job to ensure that when fictional details were added to factual events, they remained very plausible for every story told. Alden confirmed this, saying that Thorn vetted everything that was written for the project.

Did this essay of “Hoyt and the Dead Body in the Trunk” happen as I’ve written it? Probably not, as we have no first-person observations for many of the details presented. But those details, even though imagined, are nonetheless based on a very real event – one you covered so well in your book. That event is the story here. The plausible yet imagined details simply make the story more fun to read.

Thanks Ron for your insights and clarifications. I’m reminded of Babe Ruth’s Called Shot in the 1932 World Sereis. If you asked Ruth, you’d get one version. If you asked Charlie Root, the pitcher, you’d get a completely different version. Players and spectators also had differing versions. But no one disputes the basic facts: Ruth hit a home run after he pointed somewhere or at something. So that part of it really happened. But which of the versions is the correct one regarding the details?

Thanks, Gary. I appreciate your insight on this.

In your example, both Babe Ruth and Charlie Root were present for the event. Similarly here, both Waite Hoyt and Myles Thomas were present as well. However, Ruth and Root are on record describing their respective versions of the event. Whereas here, only Hoyt recorded his. Thomas did not, at least there’s no record of him doing so. The diary entry attributed to him was created almost 90 years later as part of the ESPN project, apparently to weave a plausible narrative around true events that too little was known about. For the sake of their readers, I think Doug Alden, et.al. were simply trying to bring life to the story of the dead body in the trunk (pun intended).

For this reason, it’s not just a matter of the different versions of those who witnessed the event, even if those versions might differ based on bias, fading memory or even embellishment. Here, it involves an element of fiction, created by individuals who were not part of the event, and used in my essay to further describe the actual event as it occurred.

For this I must apologize, to you and to your readers, for contributing material that wasn’t fully historically accurate. It was not my intention to compromise in any way the credibility of your website. And while I do hope your readers will enjoy the essay as written, I want each of them to know that it includes an element of historical fiction intertwined with historical fact.

Haha! No need to apoligize Ron. Any event that happened decades ago is bound to have elements of fiction intertwined with historical fact. Especially in the realm of sports!

Most of the stories going back to the era of sportswriters as our eyes , even if apocryphal, are far more interesting than the analytical s**t that passes for baseball journalism today.

Thanks, Ron for giving us a most interesting

post.. There’s a line in the movie “The Man who shot Liberty Valance”:

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”.

Thank you, Paul. I’m grateful for the support.

And yes, a great line from a great movie. Much appreciated.

Paul Doyle comes through again!

Reading the obituaries (affectionately known as the “Irish Sports Page”) in today’s NY Times , I came across an interesting term in the obituary of Pierre Nora, a French historian who coined the term “Sites of Memory”.

It refers to historiography, a study of how history has been written and interpreted and the elements of the past that a community chooses to remember and which becomes symbolic ( how we remember and forget; the potential to oversimplify or sanitize history obscuring complex or contentious aspects of the past).

I coupled that with a book I recently finished, “Inventing Baseball Heroes”

by Amber Roessner.

She wrote about how the sportswriters of the early 20th century intertwined with covering the baseball players of the era. Focusing on Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson and four eminent scribes of the era (F.C.Lane, Ring Lardner, Grantland Rice and John N. Wheeler) and the impact they and others had in molding how we view Mathewson as the “saint” and Cobb as the “sinner”

She uses the term “hero crafting” and how sportwriters compromised the emerging standards of journalism. Their efforts had a bigger goal to teach American boys to be successful players in the game of life.

Hence, my description in my last post of the term “apocryphal “ to describe their writing.

It could also apply to Ron’s post and Tim’s retort to “clarify” the Hoyt story of the “body in the trunk”.

Even the most respected sportswriter

embellished their stories at times and

their friendships with the players would be met with much clutching of pearls by the standards of scribes and readers today. In the words of Yogi Berra (or probably Joe Garagiola),

“Ya know, you never know”

Thanks, Paul. Very interesting perspective. Great points about how writers approach their writing. I’d like to learn more, so I’ll be searching for the Roessner book. I appreciate your views on all of this. Very insightful.

Very interesting, Paul…thanks!

Can I make the assumption that if this story was printed at the time it happened it would have been “buried” in the back pages?

Good one, Kevin! And I think I can say we’ve accumulated a large “body” of work commenting on this one!