Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

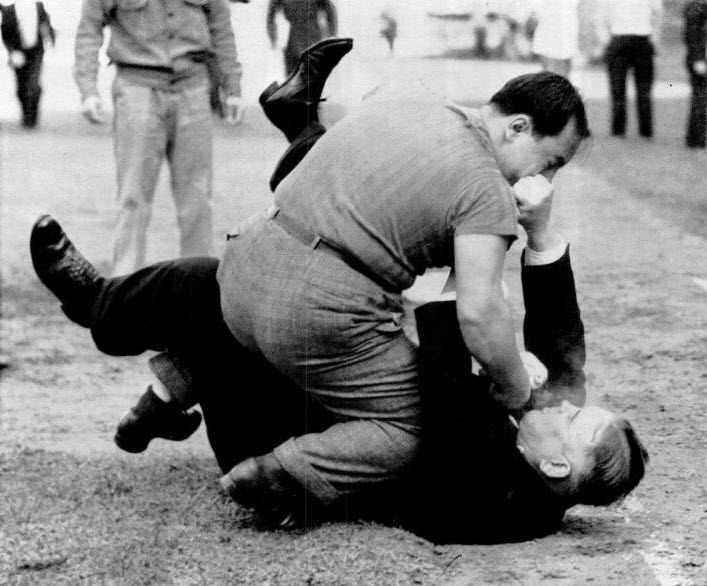

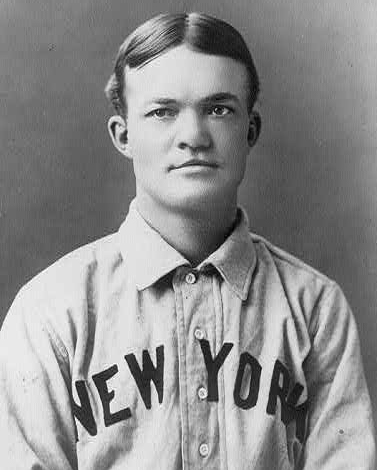

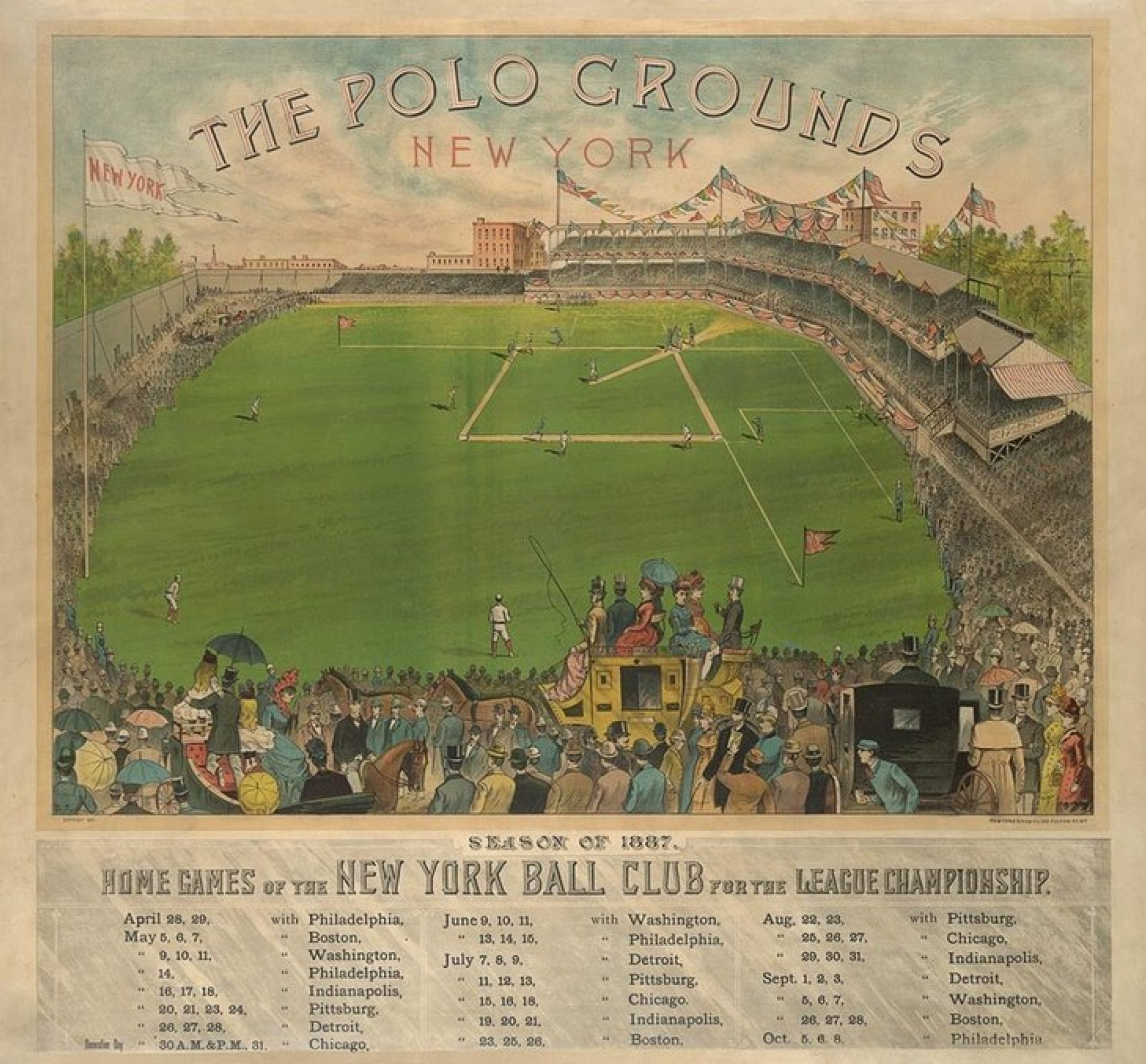

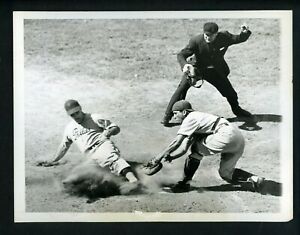

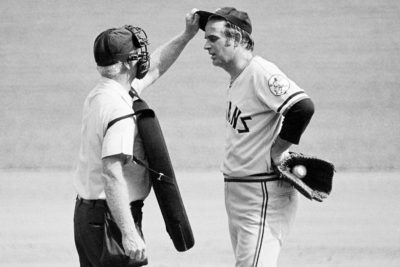

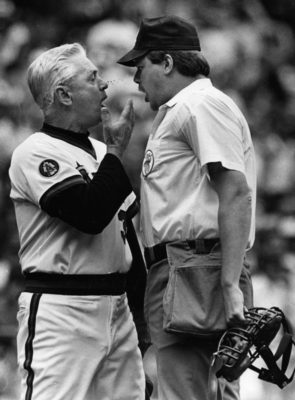

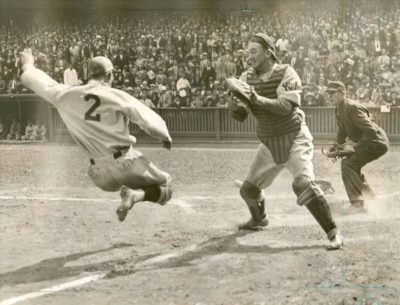

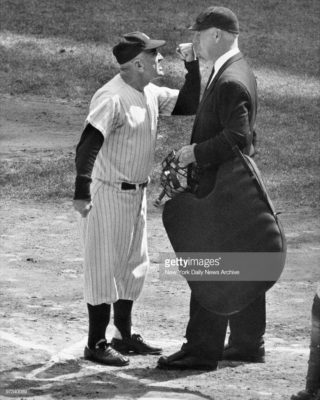

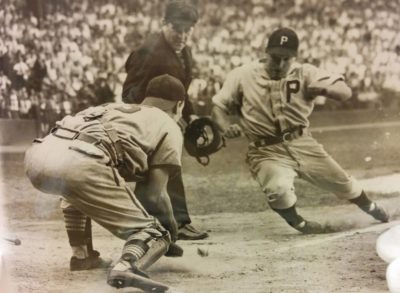

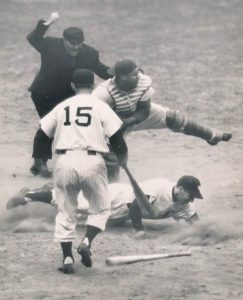

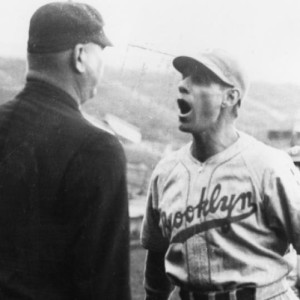

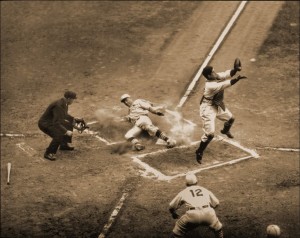

“Umpires in Action” Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Today we continue with Part Two of Thomas Marshall’s series on deaf players and the development of umpire hand signals. As I mentioned, Tom is now my “go-to guy” for all things related to the men in blue. Part One got a real nice reception from the readers, and I know you’ll enjoy Part Two too. So we’ll pick up where Tom left off…

A Historical Look at Umpire Signals and Deaf MLB Players, Part Two

“The best-umpired game is the game in which the fans cannot recall the umpires who worked it.” -HOF umpire Bill Klem

Something disconcerting to me while compiling this essay: Every deaf player in the early days of baseball had the nickname “Dummy.” In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, people who were deaf and had minimal or zero ability to speak were called “dumb.” (Though not in the sense of being stupid). In those days, if you were deaf, it was commonplace to be nick-named “Dummy.” Back then, this was not considered a rude term or one of ridicule.

In 1891, while “Dummy” Hoy was playing for the St. Louis Browns, manager and third base coach Charles Comiskey used both hands to indicate ball or strike to Hoy. A wiggle of the index finger on the right hand indicated “strike,” and a wiggle of the index finger of the left hand indicated the pitch was a “ball.” Nearing the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, more deaf players would play in the major leagues. Besides Hoy, Dundon, and Taylor, other deaf players called “Dummy” were: Thomas Lynch (1883-84), Reuben Stephenson (1892), William Deegan (1901), George Leitner (1901), and Herbert Murphy (1914). Interestingly, in 1901, the New York Giants’ pitching rotation included three deaf pitchers: Deegan, Taylor, and Leitner. This was the only time in major league history.

As deaf players continued to teach their teammates some basic ASL signals, many used what were called “finger signs” for things such as “bunt,” “take a pitch,” “steal,” “hit-and-run,” etc. Legend has it that Hall of Fame pitcher Joe McGinnity didn’t fully know enough “finger-signing” that could be understood. In frustration, he would resort to just thumb signals. Many baseball historians believe this was the origin of the phrase that a person was said to be “all thumbs.”

The first deaf major leaguer NOT to be called “Dummy” was Dick Sipek who played for one season (1945) with the Cincinnati Reds. He also taught many of his teammates basic baseball-related ASL. Once, after being called out on a very close play, Sipek “signaled” a profanity-laced protest at the umpire who, with a perplexed look at Sipek, did not understand a thing. In response to this, Sipek’s teammates erupted into roaring laughter. It was not until 48 years later that another deaf player would participate in the majors. In 1993, Curtis Pride debuted with the Montreal Expos and would have a 13-year career with six teams, finishing with the Angels in 2006.

Due to the ever-increasing popularity of baseball at the beginning of the twentieth century, larger stadiums were being built and attendance was rapidly increasing. Crowds were becoming louder and louder. In years prior, umpires only needed to render their decisions vocally. But with the larger stadiums and crowds, it was becoming more difficult for fans, players, and coaches to adequately hear an umpire’s call. It became apparent to baseball officials that the signals used by the deaf players should be used by the umpires. The idea did not catch on with universal acceptance. Many umpires balked at having to use hand and arm signals. Others, getting hoarse because of having to strain their vocal cords, were very much in favor of the physical signals.

Such was the case in the 1906 World Series, which featured the Chicago cross-town rivals White Sox and Cubs. In Game One, played at the Cub’s Westside Grounds, National League umpire Jim Johnstone worked as the home plate umpire. His “vocals-only” calls were hard to discern due to the spacious stadium and the loud, raucous crowd. His vocal cords were severely strained, and the next day he was hoarse and had nearly lost his voice. The Series moved to the White Soxs’ Southside Park for Game Two where American League umpire “Silk” O’Loughlin worked the plate using hand/arm signals the entire game. The game went smoothly and players, coaches, and fans. Everyone clearly understood each call. For Game Three, even though Johnstone’s voice had recovered somewhat, he too resorted to using hand/arm signals the entire game.

One year prior to the 1906 World Series, umpire “Cy” Rigler had been using hand/arm signals for the entire 1905 season in the minor leagues. Rigler is recognized as the first umpire to utilize hand/arm signals. By 1908, baseball officials decreed that the use of physical signals shall be used uniformly throughout the major leagues.

The next time you watch a baseball game, spend a bit more time watching the umpires and their signals. And when you do, I hope you’ll reflect back and smile for those umpire signal pioneers like Parley Pratt, “Cy” Rigler, “Silk” O’Loughlin, and Bill Klem. Also remember that it was because of “Dummy” Dundon, “Dummy” Hoy, and all of the other deaf players from the past that umpire signals are a part of the game we know today.

Thomas L. Marshall

Resources :

“The History of Umpiring” -Larry Gerlach

D.W. Anderson – SABR

“The Hidden Language of Baseball” – Paul Dickson

“Deaf Players in Major League Baseball”: A History

Jami Fisher, ASL Program Instructor, U of Penn.

Joe Guzzardi – Bedford Gazette

Photo Credits: All from Google search

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with 1,122,000 hits and over 950 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Information: Excerpts edited from

Great article. Interesting to learn the history behind the umpire signs.

Thanks for checking in Sue!