Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive! for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

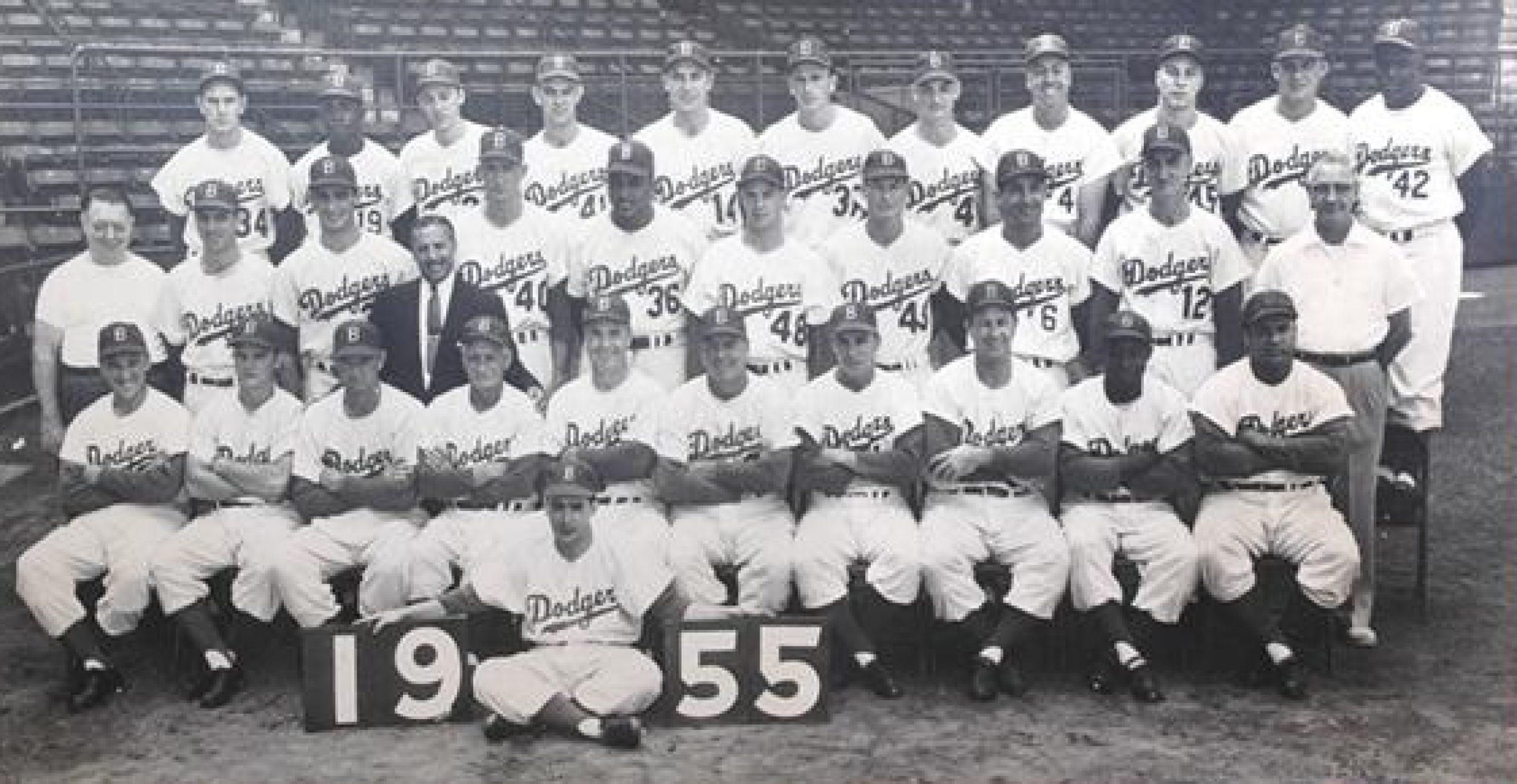

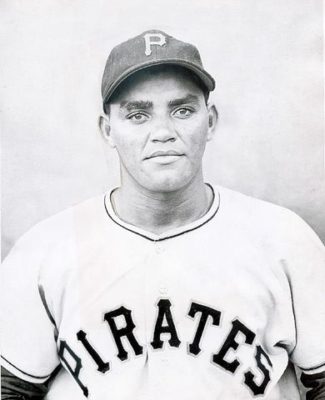

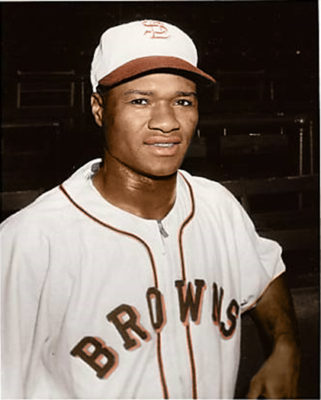

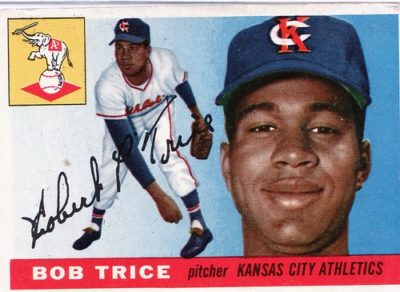

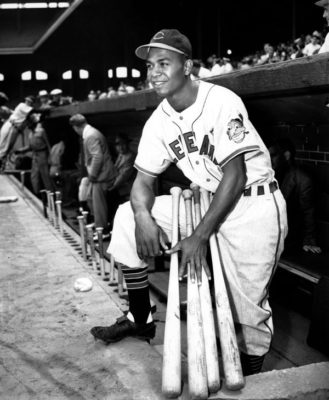

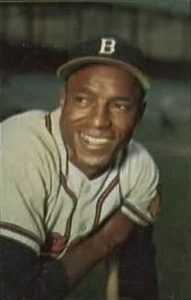

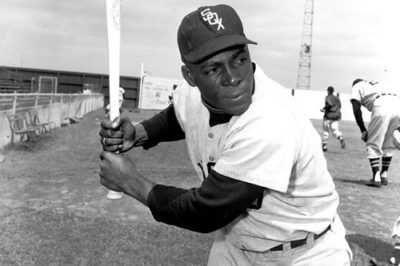

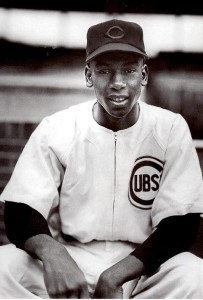

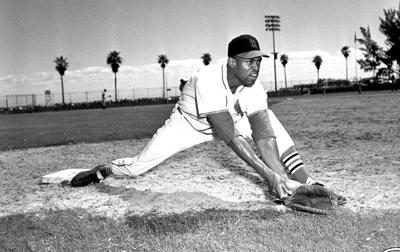

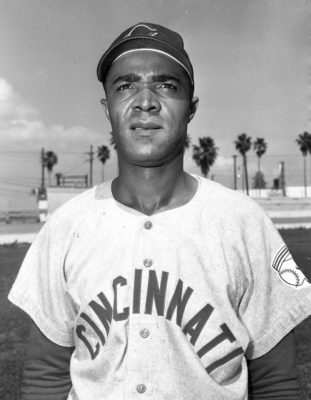

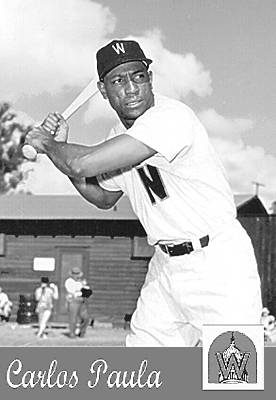

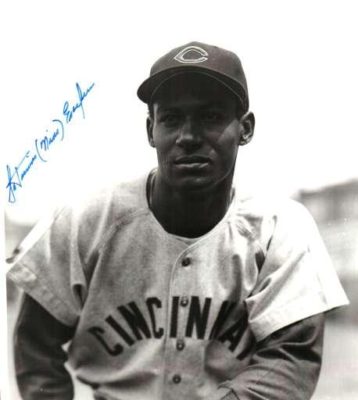

First African-American Player to Integrate Each Team Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Let’s Remember Pumpsie Green: Baseball’s Reluctant Pioneer

An obituary last month in the national newspapers got very little notice, except maybe from a few die-hard baseball history fans…

After all, how many people outside of the baseball world would you expect to remember a journeyman major league infielder who played in a total of 344 games, the last coming 56 years ago? Not to mention that in a five-year career, this journeyman hit just .246 with 13 home runs and 74 RBI in 796 at-bats?

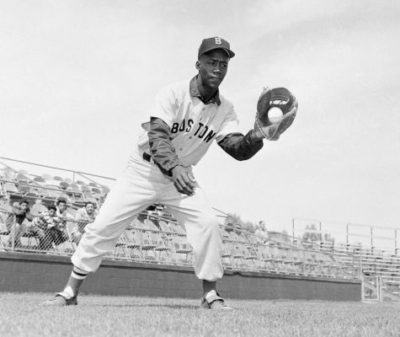

But Elijah “Pumpsie” Green, who had passed away on July 17, 2019, at age 85, will forever merit a special place in baseball history: When Pumpsie stepped on to the diamond on July 21, 1959, in the top of the eighth inning at Chicago’s Comiskey Park as a member of the Boston Red Sox, he completed the circle of full integration of all major league teams. He entered the game as a pinch-runner for Vic Wertz and stayed in to play short. The historic moment came a full 12 years after Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s odious color barrier.

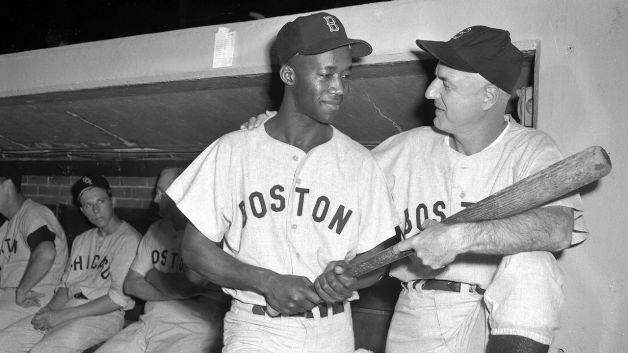

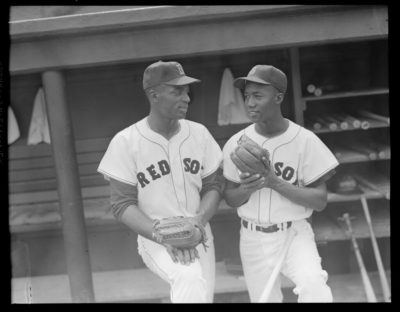

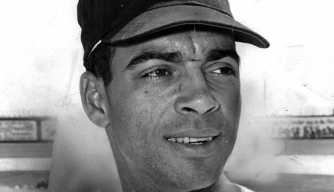

In the featured photo above, we see Pumpsie Green with Red Sox manager, Billy Jurges, 1959.

First a little background:

We’re all familiar with Jackie’s trials and tribulations as the first racial pioneer to integrate major league baseball in 1947. After he opened the door, slowly but surely other clubs began tapping into the available pool of talented African-American players. These were ballplayers who had been denied a chance to prove that they were equal—and oftentimes superior—to the legions of white ballplayers that had exclusively constituted the big leagues.

As the decade of the 1940s turned the page into the ‘50s, there were still teams that had not recruited black players. Teams like the Chicago White Sox incredulously made statements that there were “no good black ballplayers to sign.” The Boston Red Sox likewise went through motions that were politically driven, as they gave the “bum’s rush” to both Robinson and Sam Jethroe in staged tryouts. Then they could say: “Hey, we tried.”

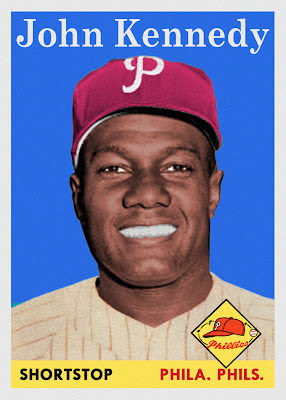

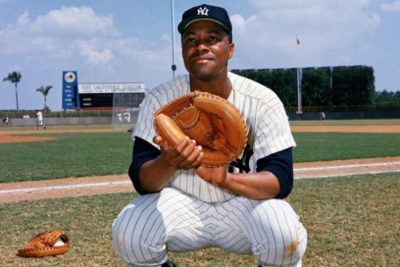

By the mid-to-late-Fifties, most of the major league holdouts had signed black players: Elston Howard with the Yankees in 1955; John Kennedy with the Phillies in 1957, and Ozzie Virgil, Sr. with the Tigers in 1958. That left the Red Sox as the lone major league team not as yet integrated.

Back in 1948, owner Tom Yawkey added Birmingham, Alabama as a location for one of his farm teams. Of course, the Birmingham Barons were an all-white team. Sharing the same historic ballpark with them were the Birmingham Black Barons. They had a young ballplayer named Willie Mays on their roster. According to sportswriter Howard Bryant, one of the conditions for their lease of Rickwood Stadium was that the Red Sox had first crack of the Black Baron players.

Willie Mays was attracting so much attention that Red Sox Manager Joe Cronin finally dispatched one of his scouts to take a look. The legend goes that weather postponed games for three days, and the scout griped, “I’m not going to waste my time watching [these players].” The scout then filed an unenthusiastic report without ever watching him play. The Red Sox had missed out on a chance to land Willie Mays.

Due to the racial attitudes of people employed in the organization over a decade after the arrival of Jackie Robinson, the Red Sox still had no organizational plans for integration. How much of this reluctance to sign black ballplayers was the fault of owner Tom Yawkey? We’ll never know for sure; but, as team owner, a large share of the blame must fall on his shoulders.

If you’ve been a Boston Red Sox fan for any length of time, you know Yawkey’s tenure was filled with contradictions. He has often been accused of being a racist; and, in the era of revisionist history and political correctness in which we find ourselves, new ownership worked behind the scenes to get Boston city officials to change Yawkey Way back to the original Jersey Street.

SABR Vice President Bill Nowlin attempted to write a balanced biography of Yawkey last year. He was criticized in some circles because he presented viewpoints that did not jive with prevailing political sensitivities about Yawkey, e.g., that he was a racist and did not deserve anything positive being said about him.

Meanwhile, back to Pumpsie Green…

Being the last of the integration holdouts, the Red Sox invited Pumpsie to Spring Training in 1959. He had been in their minor league system since 1956. Pumpsie hit .400 that Spring and was cited as “Camp rookie of the year”. But alas, at the end of camp, he was assigned to Triple-A. This led to more racial accusations and even picketing at the ballpark.

Finally, on July 21, the 6’, 175-pound switch-hitter was called up and he made his historic debut with the club. His first major league hit, a single off Jim Perry, came on July 28. That same day, pitcher Earl Wilson made his major league debut, becoming the Red Sox’ second black player. A few days later, on August 4, Pumpsie debuted at Fenway Park, collecting a triple in his first at-bat.

His subsequent four years with the Red Sox were spent as a part-time player. He was quietly dispatched to the second-year New York Mets in 1963 where he spent another less-than-stellar year before retiring at the end of the season.

Following his playing days, Pumpsie worked at Berkeley High in Berkeley, California. For over 20 years, he served as a truant officer, baseball coach, and math teacher. On April 17, 2009, he was honored by the Red Sox in recognition of 50 years since breaking the Red Sox color barrier. In April 2012, he was invited to throw out the ceremonial first pitch before Jackie Robinson Day at Fenway Park; and he also attended Fenway’s 100th anniversary celebrations later that month. In May 2018, Pumpsie was inducted into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame.

To many long-time Boston Red Sox fans and other proponents of social justice, Pumpsie Green was more than a journeyman ballplayer. Aware of his place in baseball history, he was, as he stated himself, a “reluctant pioneer,” who completed the circle of integration for major league baseball while always handling himself with quiet dignity.

Rest in Peace, Pumpsie Green.

Paul Doyle

Sources: Boston Globe; article by Bill Nowlin, “Tom Yawkey: Patriarch of the Boston Red Sox”; Howard Bryant’s, “Shut Out: The Story of Race and Baseball in Boston”; and the Pumpsie Green Wikipedia page.

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. Click here to view Amazon’s privacy policy

A couple of unfortunate errors in the photos accompanying this article:

1) Sam Jethro was 1950, not 1960;

2) photo of Elston Howard is backwards.

I grew up in a Boston suburb and can remember when Pumpsie Green joined the Red Sox. He was definitely not the stongest player to break the color line in Boston. I also remember when he joined Red Sox pitcher (and Celtics reseve center) GHene Conley on thier ill fated trip to the Holy Land.

Too bad Mr. Yawkey did not allow the signing of Henry Aaron or other African American who were given perfunctory try-outs by the Sox. I was in Boston last week and saw, in person, that Yawkey Way has reverted back to its original name, Jersey Street.

Thanks for catching the typo on Sam Jethro, will correct. I’d be surprised if that’s the only one. And I flipped the Elston Howard pic.