Featured Panoramic Photo Above:

Classic Charles Conlon photo of Ty Cobb sliding into Jimmy Austin

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

My Review of:

Bright Lights Black Stars

“I owe more to Canadians than they’ll ever know. In my baseball career they were the first to make me feel my natural self… “ -Jackie Robinson

If you’re like me, when you think of Canadian sports, the first image that comes to mind is, of course, their national game of hockey. But how many baseball history fans are aware that since the earliest decades of the twentieth century, there has been a thriving baseball world just north of us in Canada?

I wasn’t aware of any of that, that is until I was contacted by Paul Allen and was asked to read his eye-opening book, Bright Lights Black Stars. Before I read it, my knowledge of Canadian baseball consisted of recalling that Hall of Famer Fergie Jenkins was a native of Chatham, Ontario. Maybe that’s just a testament to my American baseball bias. Just to give you a small sampling of what I learned about Canadian baseball from Bright Lights Black Stars, did you know that:

- The first recorded baseball game was played in Canada?

- Base Ruth hit possibly his first professional home run in Canada?

- Babe’s first baseball coach and long-time mentor was Brother Mathias, a Canadian?

- Hundreds of former Negro Leaguers and former major leaguers played baseball in Canada?

- Canada is the home to the oldest, continuously-operating league in the world?

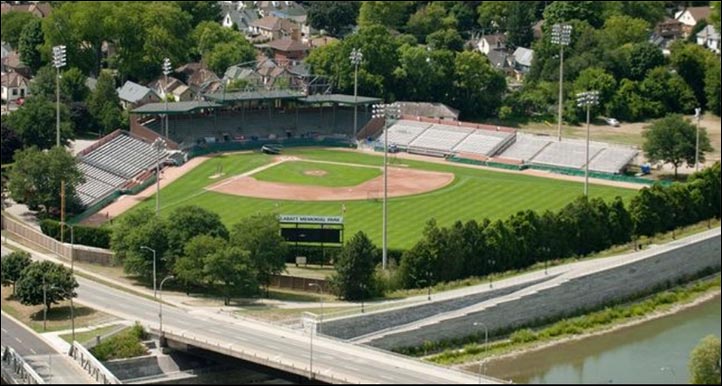

- Labatt Memorial Park, home of the London, Ontario Majors, is acknowledged as the longest-continuously played diamond in the world?

All this and much more is detailed in Paul Allen’s book which highlights the rich history of Canadian baseball with a focus on the Intercounty Baseball League (IBL) in Southwestern Ontario during its Golden Years from 1948 to 1958. Founded in 1919 with four original teams (Galt, Guelph, Stratford, and Kitchener), the IBL is the longest continuously functioning baseball league in existence. In 2018, it celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary, now with eight teams, including Paul’s hometown of Chatham, Ontario.

A fine ball player himself, Paul Allen has fond memories of playing baseball in racially tolerant Southwestern Ontario. He remembers one of his friends calling Chatham, “the United Nations of baseball teams”:

“In my hometown of Chatham, Ontario kids were really not race conscious. They just wanted to play ball and it mattered not who was on our team, what they looked like or what was their background. We could care less. Chatham’s ball teams were composed of players whose parents and grandparents came from various nations around the world. We had players that descended from American runaway slaves. We had players of Japanese and Chinese origin. We had an assortment of kids who could trace their genealogy from Britain, Poland, Germany, Holland, Scotland, Ireland, and from lots of other countries. We had Protestants and Catholics on the teams…The lessons learned helped us in later life to respect all people and work together in a team atmosphere…It’s thanks to [the city of Chatham, Ontario], and the coaches that a considerable number of boys who went through the city’s baseball system grew into responsible, racially tolerant, and successful citizens. I’m eternally grateful to have lived and played baseball in my formative years in this city.”

One particular game played in North Buxton, a community originally settled by runaway slaves, left an indelible impression on Paul’s young mind:

“One of my great baseball memories in an integrated setting is a good example of how all people can treat each other. Our Pee Wee All Stars had an exhibition game in 1954 against an entirely black team from Detroit, Michigan…The game was held close to Chatham in the small settlement of North Buxton as part of the village’s Annual Homecoming and Labour Day celebrations. Buxton’s inhabitants are ancestors of runaway slaves who settled in the area before and during the Civil War. Nearby Windsor was the final terminal of the Underground Railroad, so the Buxton farming community on the shores of Lake Erie gradually became populated with escaped slaves who fled North during the war years. Buxton park was packed with locals all awaiting the game. The crowd was predominately black and our white parents and friends sat quite comfortably in the stands. There were no racial incidents at all. Everyone got along simply fine…”

That’s quite a testament to Canadian baseball. The Intercounty League attracted players not only from the Negro leagues, but also from colleges, semi-pros, and even former major league players. But as I read the book, I couldn’t help but be struck with a sense of sadness. I kept thinking about the treatment of black ball players in the United States in the early decades of the twentieth century and the overt racism and humiliating hardships that they endured. We’ve all heard the stories of Negro League ball players being relegated to inferior “blacks only” hotels and segregated restaurants, often forced to sleep on their buses when deprived of suitable accommodations as they traveled from city to city to play the game they loved. From our perspective many decades later, it’s hard for us to comprehend that such blatant racial prejudice existed.

I was surprised to learn that virtually every Negro League star at some point played ball in Canada, including some of its greatest stars like Satchel Paige. Paul details many of their outstanding careers. One in particular, Wilmer Fields, may have been one of the greatest players ever, but almost no one in America has ever heard of him. It’s no wonder that many black players looked to Canadian baseball as an alternative, “safe haven,” with over 300 Negro Leaguers at one time or another filling the rosters of Canada’s many different teams and leagues. It’s also not surprising that many of them returned to Canada after their playing days ended and became permanent residents. What a tragedy that — with just a handful of exceptions — virtually none of these stars were permitted to play professional baseball at the major league level in their own country:

“Canadian teams, white players, and fans were noticeably different from those the Negro League players encountered in the southern states and in some places in the North. Any evidence of racism or discrimination in the Canadian Leagues seemed trivial or almost nonexistent to black players compared to what they faced in many places in the United States. Jackie Robinson paid tribute to the Canadian experience when he said: ‘I owe more to Canadians than they’ll ever know. In my baseball career, they were the first to make me feel my natural self and the fans there (Montreal) were just fantastic, and my wife and I had nothing but the greatest memories.’ “

Paul has interesting information about his friend and former Chatham teammate, Fergie Jenkins. The two go all the way back to Bantam and Junior ball. They played together on three Ontario Baseball Association championship teams and even attended major league tryout camps together. The city of Chatham — and all of Canada — is rightfully proud of Fergie as its first Hall of Famer. I was surprised to learn that Fergie, like most Canadian youths, was an accomplished hockey player. He was skilled enough to practice with the Chicago Black Hawks during his time in Chicago, although Paul makes clear he made the right choice in pursuing a baseball career. After his retirement, Fergie returned to Canada and pitched for two years (1984-85) in the IBL.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of recounting the stories of all the outstanding players, black and white, who enjoyed the experience of baseball in Canada. As we baseball history buffs progress in our knowledge of the game, Canadian baseball has been a neglected chapter in that long history. Paul Allen’s outstanding book, Bright Lights Black Stars, is one I can heartily recommend to all of us to fill that glaring gap in our knowledge. It’s a book for all who love the game of baseball and want to learn more about its past, especially about baseball “North of the Border.”

Gary Livacari

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with 1,117,000 hits and over 950 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Enjoyed this post, Gary. Of course, I knew about Jenkin’s baseball origins in Canada, but this article revealed lots of other facts unbeknownst to me prior to reading it. A bit confused about the “black Canadian player who broke the color barrier for the Cleveland organization on 7/4/1948″ though ????? Larry Doby’s debut with the Indians was shortly after Jackie’s Robinson’s Brooklyn debut on 4/15/47. Doby’s first game for Cleveland was in July 1947. And he was not from Canada. {Born in the Deep South, I think}. BTW, In 2010, I was one of the umpires @ a youth WS near Detroit {Taylor}. One of my colleagues on our 12-man crew is from Calgary. He told me that youth and high school baseball is thriving there; despite {as you said} that country’s love for hockey. Thnx for the BHCA insight, ……”Great White North” style.

You know, I took that line right out of the book. I agree, it was confusing to me too, but I just thought i was missing something. Mybe Paul meant by “organization” the minor league sytem. Maybe Paul will see this and clarify. In the meantime, I think I’ll just take it out of the essay.

Sorry for the late response. When I wrote about the first black player to sign with the Cleveland Indians “organization” (that being Canadian Freddie Thomas), I did not mean to imply that Freddie was the first black player to appear in the MLB for Cleveland. Freddie Thomas was the first black player to sign “into” the Cleveland organization and was assigned to the Wilkes-Barre team in the Eastern League. He was the first black player to integrate the Eastern League and consequently the first to integrate the Cleveland Indian organization. Of course, Larry Doby was the first black player to play for the MLB squad.