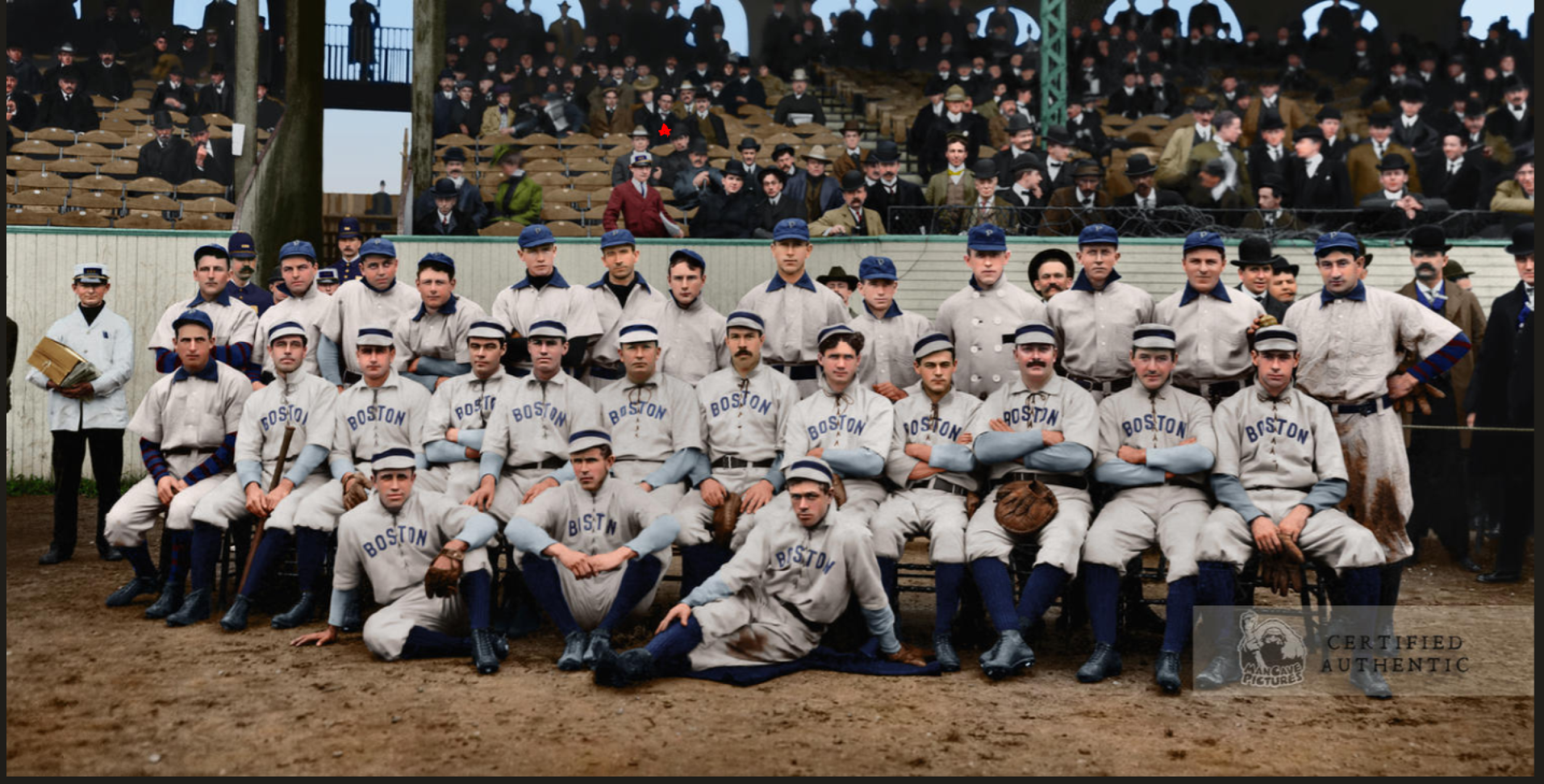

Featured Photo Above:

Combined 1903 World Series Photo: Pittsburgh Pirates and Boston Pilgrims

(Color Restoration by Chris Whitehouse of Mancave Pictures)

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive! for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

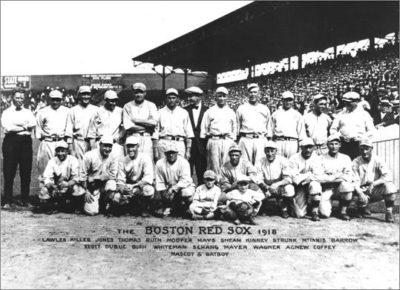

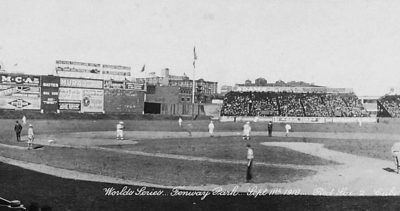

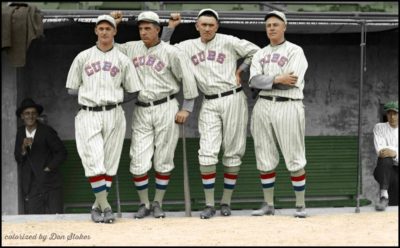

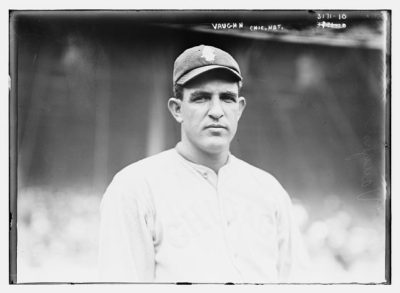

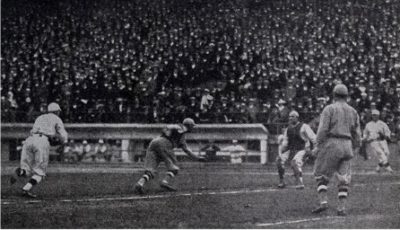

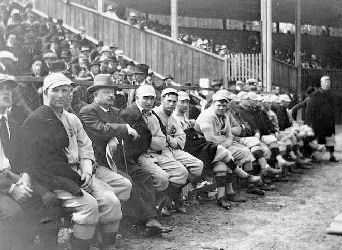

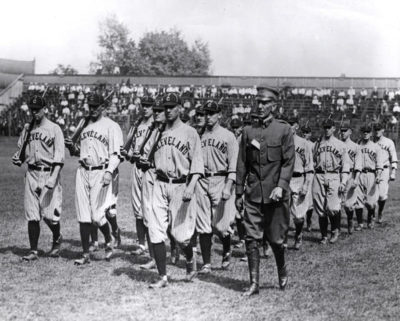

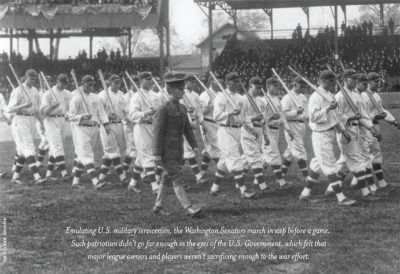

World Series and the Pandemic of 1918 Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Today we welcome back Paul Doyle to Baseball History Comes Alive with an interesting essay about a previous pandemic that greatly affected a baseball season, including some of its biggest stars. And, as the featured photo clearly shows, it is possible to play baseball while wearing a mask! I think you’ll enjoy the information Paul shares with us -GL

BASEBALL AND THE PANDEMIC of 1918

As we sit at home waiting to see if baseball will be played in these unsettling times, our attention turns from hitting percentages to virus fatality percentages and hope that it stays way, way below the Mendoza line.

Many of us who are baseball historians also love history in general. What we may not remember is that the Spanish Flu of 1918 had more of an impact than we realized. It also touched two of the biggest stars in baseball history in a roundabout way.

Even though it was called the Spanish Flu, it had nothing to do with Spain. In fact, the world was in the middle of the Great War and the news of the day was focused on that event. Unlike today, the news media was prohibited from publishing certain items of interest, especially if the government perceived it would have a negative impact on the morale of the armed forces or the country in general. It is hard to believe in today’s media-driven society that the first amendment was so strongly monitored and controlled by the government, not the so-called Fourth Estate. The atmosphere was very anti-immigrant and the draconian Sedition Act of 1918 was used as a crutch at times to stifle the press.

What’s that got to do with baseball you ask? There is some debate as to where the pandemic began. Some think it was in France and was brought into this country by the back-and-forth of armed forces from Europe. Other experts believe it started somewhere in Kansas and was spread by the general movement of people, especially those that were in basic training for the military.

In March of that year, several thousand doughboys were struck down while training in Camp Funston in Kansas. For thirty-eight of them, the disease was fatal. After their basic training, those not sick (we would use the term “asymptomatic” today) were transferred to military camps across the country by train, including Camp Pike in Arkansas and Camp Devens in Massachusetts. That year, the Boston Red Sox team held spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

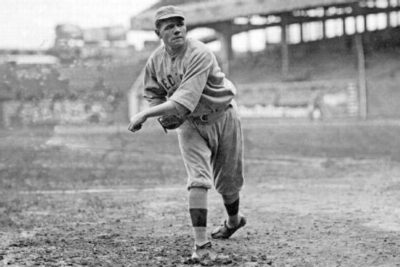

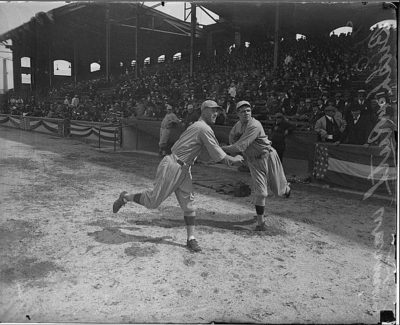

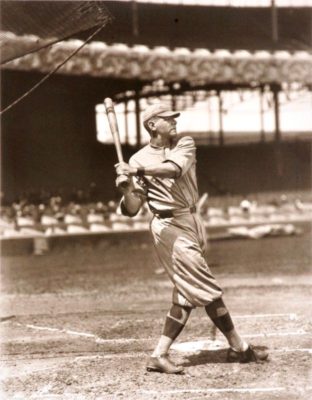

As the flu was spreading, the ballplayers were hopping trains to their spring training camps. As the Sox made their way to Arkansas, reports indicated every stop on the way had soldiers boarding ready to report for duty. Even in those days, Babe Ruth was the star of the show, glad-handing and stopping to talk to anybody; and according to the Boston Globe’s beat reporter, Ed Martin who was on the same train heading to camp, Ruth “was the life of the party and fraternized with a lot of the soldier boys from Camp Devens.”

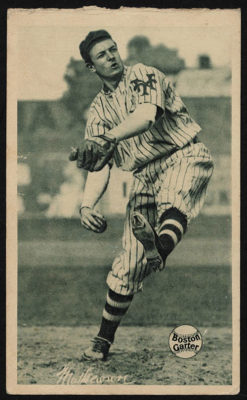

The Babe at that point in his career was more valued as a pitcher than a hitter. It was still the Dead Ball Era and the scientific game of small ball still held court. The Sox roster was impacted by the departure of some of the players in the war effort. Manager Ed Barrow was of that school and when the Babe started uppercutting and hitting balls out of the park, he considered it a circus act.

As spring training proceeded, the team seemed to get hit hard by the “grippe.” Reporters had noted that the city itself was in the middle of an epidemic of sickness. While nobody was seriously impacted, the brass in Camp Loring contacted the U.S. Public Health Service to report a deadly strain.

The season started up North with no apparent effect from what they experienced in Arkansas. In mid-May, the Babe took his wife Helen to the beach on an off day. It was the first warm day of the spring. Babe mixed in with the other beachgoers and even played a game of sand baseball.

It was that night that Babe became ill. He had the chills, a temperature of 104 degrees, ached, and shivered. He survived the night and reported to Fenway Park the next day looking like a ghost. The team doctor took one look at him and sent him home for bed rest. The doctor accompanied him and treated him for his sore throat, swabbing him with the prescribed treatment of the time: silver nitrate. It is believed that he received almost a fatal dose and had a violent reaction. He was taken to Mass. General Hospital for treatment. It was misreported that the Babe was suffering from tonsillitis, and some newspapers even reported he was on his deathbed.

Ruth was laid up for almost a month. He returned near the end of June. The country’s involvement in the Great War was now in full swing. With the warmer weather, the flu seemed to wane. That is, until the second wave of the epidemic reared its ugly head in late August. Baseball tried to implement some safety measures and one of them was to ban the then-legal spitball for sanitary reasons. Some players wore masks. Baseball also announced that the season would be cut short and end on September 1. The official reason was to put all efforts towards the war. The flu began raging at Commonwealth Pier, a naval destination for arrivals and departures for troops.

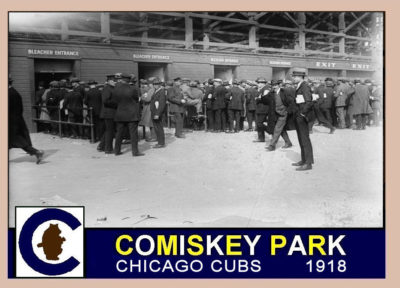

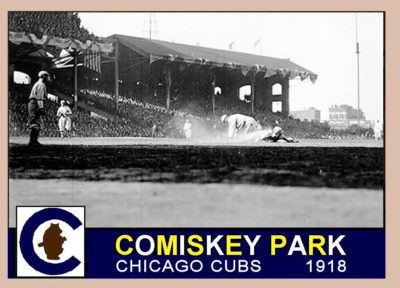

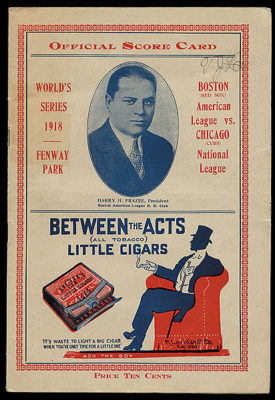

On September 3, over four thousand people, including troops from Commonwealth Pier marched in a “Win the War for Freedom” parade in Boston. Mixing with civilians, the parade led the spread throughout the city. The State Department of Health issued a warning about the spread of the disease. The World Series began two days later in Chicago. There was no shelter-in-place back in those days. A warning was a warning.

The teams returned to Boston on September 9 to resume the Series. Remember, there were no prohibitions for “social distancing.” There were three World Series games, rallies, and draft registration. People rode trollies and subway cars everywhere. Some thought that the disease was centered on the area around the Pier.

There was some cognizance since the crowds over the three games diminished to the point that only 15,000 showed up for the last game. There were grumblings of a strike by the players on both sides because players’ shares of the gate were reduced.

The Series ended with the Sox victory over the Cubs. There was no victory parade. The epidemic spread rapidly. By September 25, 700 citizens of Boston were dead from the flu. On September 26, the mayor finally closed all theatres, concert halls, and other places of assembly. A little late. By October 20, 3,500 had died and the second wave was over. Sailors and soldiers were still departing for Europe during that period, becoming an incubator for the disease.

In early October, Ed Martin, the beat reporter for the Globe who had reported on the train trip to Arkansas and covered the team for the season and the World Series had died of the influenza.

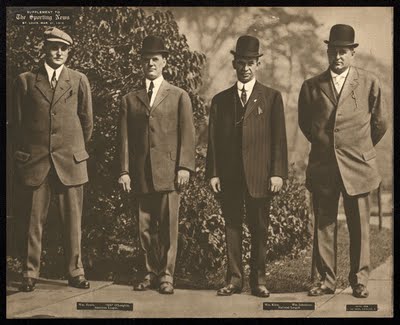

One of the umpires in the Series, one of the more respected ones in the game, was Silk O’Loughlin. He was the umpire who called one of the Series games because of darkness. It has gone down in history as the only Series game that ended in a tie. Rules at that time did not suspend games to resume the next day.

At the end of the Series, the government ordered people to find “essential work.” O’Loughlin worked for the Treasury Department that offseason and, ironically, was assigned to the Boston office. In December, he caught the flu and died.

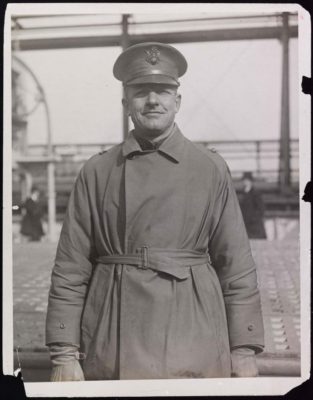

As this was all going on, Christy Mathewson’s playing career was over. Managing the Cincinnati Reds at that time, he volunteered for duty at the age of 38. We all know that he was accidentally injured with poisonous gas while training soldiers in the proper use of gas masks overseas. What is sometimes forgotten is that Mathewson, like all troops, was assigned overseas by ship. During the voyage over to Europe, Matthewson caught the flu and was deathly sick for almost ten days before he recovered.

As with most of history, “past is prologue.” We all are hoping that this current pandemic can run its course and we can look back on it years from now as we sit down on a warm summer night with a beer in our hand watching the national pastime.

Paul Doyle

Sources: Baseball Hall of Fame; Rochester, NY Business Journal (Scott Pitoniak); “War Fever: Boston, Baseball & America in the Shadow of the Great War (Randy Roberts; Johnny Smith)

Add your name to the petition to help get Gil Hodges elected to the Hall of Fame

Vote In Our New Poll: Baseball and the Coronavirus – What Constitutes a Legitimate Season?

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. Click here to view Amazon’s privacy policy

Thanks, Paul, for a most interesting and timely essay. Pictures of the batter in the mask and the Babe in uniform are priceless.

Would that we might have a little less media coverage with today’s pandemic-talk about a downer for morale, on a daily basis!

It’s a small world. When Christy Mathewson was accidentally exposed to poisonous gas while training soldiers in France, he became susceptible to tuberculosis. Christy spent some time in Saranac Lake, New York, where he played checkers with my grandfather. Both were being treated for the disease in the early 20’s. My dad said his pop liked Matty and referred to him as, “A real gentleman.”

Yeah, hoisting a tall cold one while watching the Mets beat the Yankees would be nice!

Best,

Bill

Best,

Bill

Great info, Bill…thanks!

https://www.si.com/.image/c_limit%2Ccs_srgb%2Cfl_progressive%2Cq_auto:good%2Cw_700/MTczMzgyNTQwMjE4ODY5NTIy/1918-daily-cover-v.jpg

Thanks,Bill.

Due to the length of the story, one of the items edited from the story did mention his recuperation at Saranac Lake.

It mentioned that Marty often

spoke to boys groups throughout his career and was a veritable Frank Merriwell in the flesh. While recovering from his war injury at Saranac Lake in upstate New York, reporters caught him playing catch with a group of boys. They asked Matty what advice he had for them. He said that they should play baseball and learn from it and extended the philosophy of his life, which came from the book of Ephesians.

“Be humble and gentle and kind”, he replied.Ninety years later, a son of a ballplayer, Tim McGraw had a hit recording of “Always be humble and kind”. Both Matty and the singer’s father both were famous for their screwball pitch (called the fadeaway in Matty’s day). Oh, yeah! Coincidence that the Manager that Big Six played his entire career was a McGraw?

I’m having more and more doubts that we will be watching baseball any time soon, unfortunately.

Thank goodness for sites like this where we can replay the memories of the game.

Before I even read this, THANKS!

GREAT stuff Bill, Gary and Paul! One of the best pieces of historical fiction was “The Celebrant” by Eric Rolfe Greenberg, written in 1983 about Christy Matthewson and the NY Giants when they were the toast of the town. Highly recommended reading. I honestly believe it would have been a better movie than “The Natural” (which I did love) but the production never came to fruition.

I have that book, but haven’t read it. So I’ll pull it out!

I have a question, in the SABR biography of Christy Mathewson it said that he was

taught the fadeaway (screwball) from a old teammate, Dave Williams of the Boston

Americans. But in Ken Burns’ Baseball, it was said that he learned the pitch from Rube

Foster. Who is right? Thanks for any help.

Sean Green

Sean,

There’s no proof anywhere that Foster taught Matthewson the fadeaway pitch.

Mathewson says he learned the fadeaway in 1898 while pitching for the semi-pro Honesdale (PA) club.

That’s what I believe. The Foster rumor appears to be just that.

Paul, what a wonderful article, and an opportunity to reconnect, as in the past, you commented on my blog theprogressiveprofessor.com.

This is an excellent article, and I want to congratulate you on it, and it should be shared widely.

Ron Feinman

Thanks, Professor.

If memory serves me right, you’re an old Brooklyn Dodgers fan. You can find

many reminisces on this site from fans and scholars of Dem Bums.