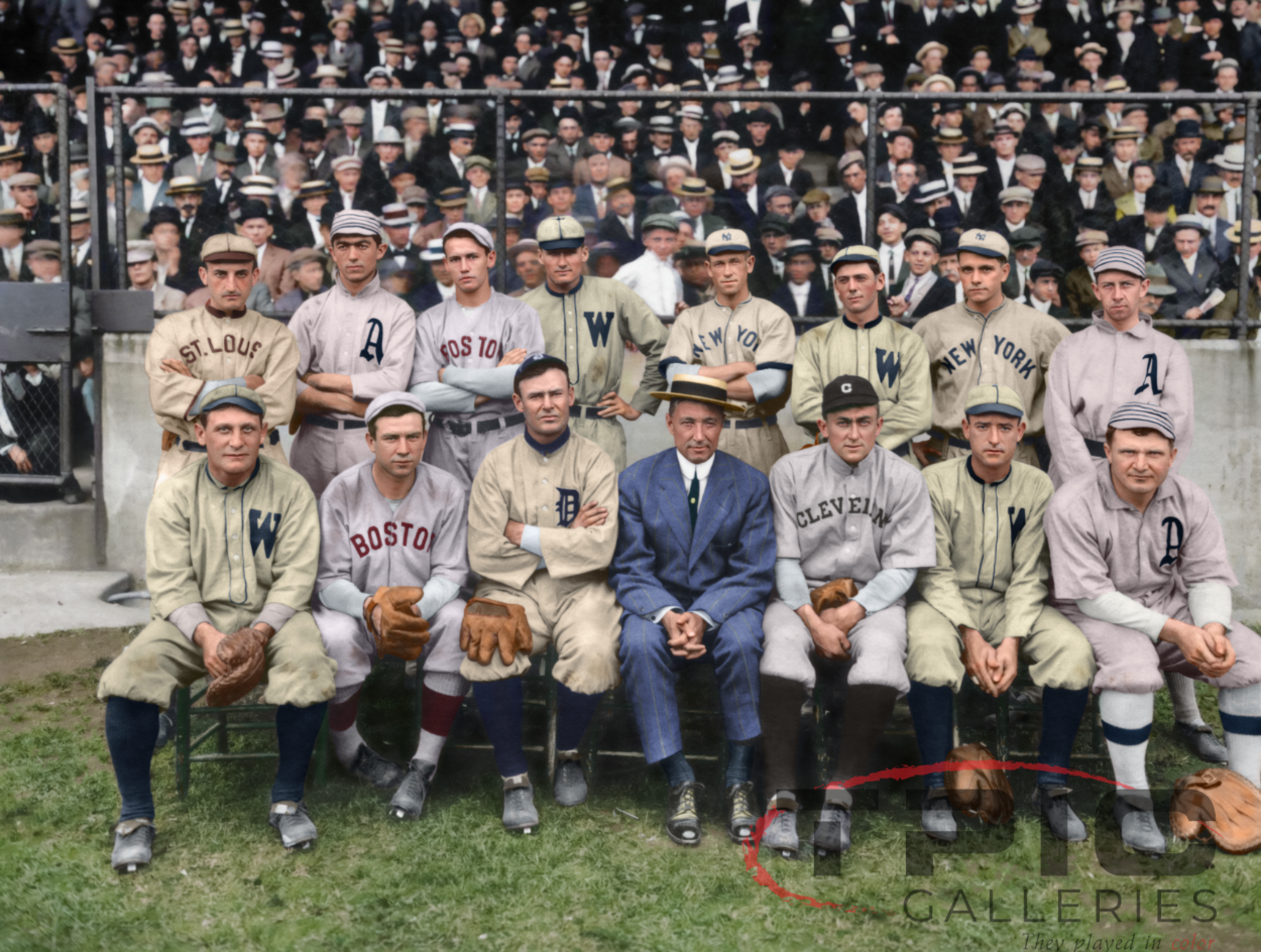

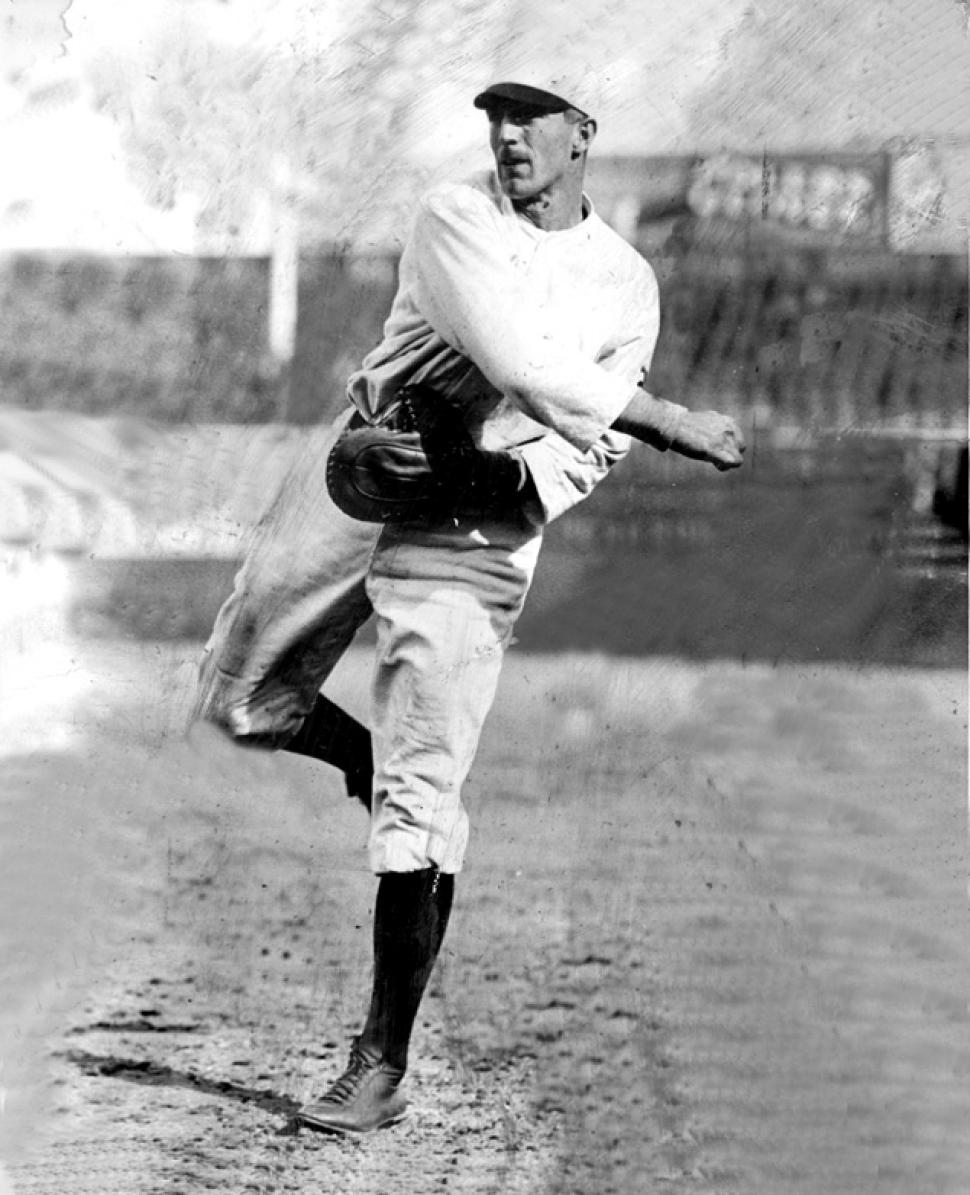

Featured Photo Above:

Addie Joos Benefit Game, July 24, 1911

(Color Restoration by Chris Whitehouse of They Played in Color website)

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Subscribe to my blog for automatic updates and as a Bonus get instant access to my two Free Special Reports: “Memorable World Series Moments,” and “Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!”

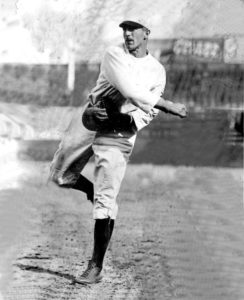

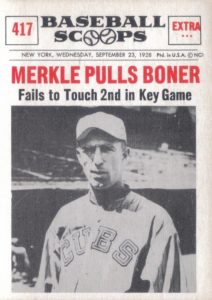

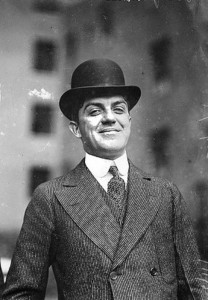

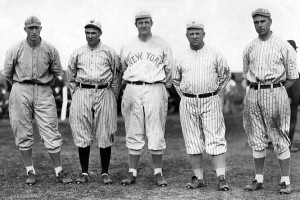

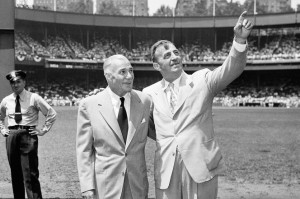

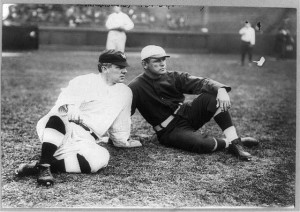

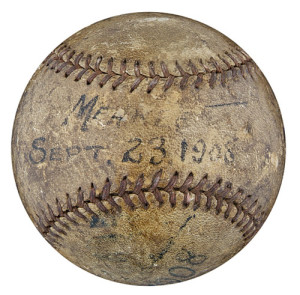

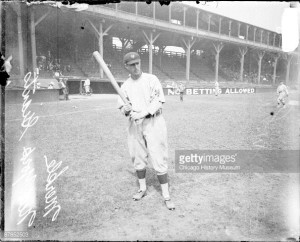

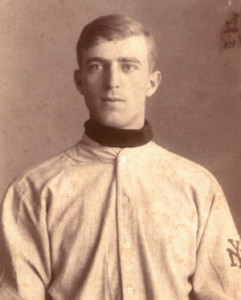

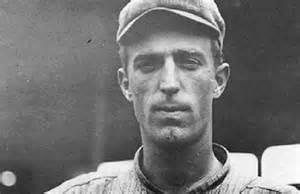

“Tribute to Fred Merkle, Part Three” Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to start gallery:

The Merkle Incident, Part Three: It’s Time to Right a Historic Wrong!

“I wish I’d never gotten that hit that set off the whole Merkle incident. I wish I’d struck out instead. It would have spared Fred a lot of unfair humiliation.” -Giant Al Bridwell, whose hit led to the Merkle incident.

In Part Two of my series on the tragedy of Fred Merkle, I left off with the “Warren Gill Game,” played on September 4, 1908. It was eerily similar to the “Merkle Game” just three weeks later. Gill’s failure to touch second base in that game set off a chain reaction with tragic consequences for a 19-year old rookie named Fred Merkle.

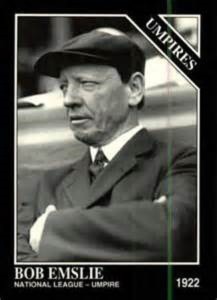

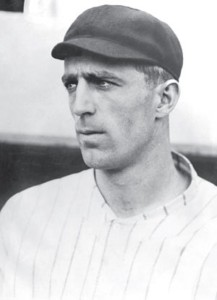

On September 23, 1908, the Cubs and Giants were tied for first place and the Pirates were 1.5 games back. Fred Merkle, the youngest player in the National League, had appeared in only 38 games. On that morning, Fred Tenney, the Giants’ regular first baseman, woke up with a case of “lumbago,” and manager John McGraw penciled in Fred Merkle to replace him. It was his first big-league start. Christy Mathewson started for the Giants against Jack Pfiester for the Cubs. The game had only two umpires: Bob Emslie on the bases and Hank O’Day behind the plate. It was scoreless through four innings until Joe Tinker hit an inside-the-park home run in the fifth. The Giants tied the game in the sixth on Mike Donlin’s single which scored Buck Herzog. The game was remained tied 1–1 when the Giants came to bat in the bottom of the ninth.

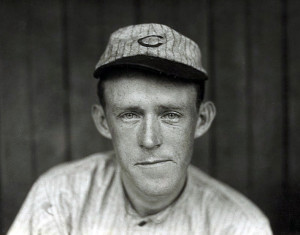

After Cy Seymour grounded out, Art Devlin singled. Moose McCormick then grounded sharply to second, but Devlin’s hard slide prevented a double play and McCormick reached first safely. With two outs and McCormick on first, Fred Merkle singled down the right-field line with McCormick advancing to third. Next up was Al Bridwell who hit Pfiester’s first pitch for a sharp single to center. Umpire Emslie was knocked on his “keister” avoiding the ball as McCormack scored easily from third with the apparent winning run.

But wait! As Giants’ fans poured out of the stands and mobbed the field, Merkle, advancing from first base, veered toward the club house without touching second. In 1908 it was customary not to appeal to an umpire for enforcement of the force-out rule on walk off hits and Cubs’ second baseman Johnny Evers, the protagonist in the Gill game three weeks earlier, saw an opportunity to have the rule enforced. Here’s what happened next:

“Evers shouted to center fielder Solly Hofman, who, amid the chaos caused by thousands of celebrating Giants fans, retrieved the ball and threw it to Evers. According to one account, Joe McGinnity, who was coaching first base that day, intercepted the ball and threw it away into the crowd of fans. Evers retrieved the ball—or found a different ball—and touched second base. Umpires Emslie and O’Day hurriedly consulted and O’Day, who saw the play from home plate, ruled that Merkle had not touched second base, and on that basis Emslie ruled him out on a force and O’Day ruled that the run did not score. The play was immediately controversial. Retelling the story in 1944, Evers insisted that after McGinnity had thrown the ball away, Cubs pitcher Rube Kroh (who was not in the game) retrieved it from a fan and threw it to shortstop Tinker, who threw it to Evers. Five years later, Merkle admitted that he had left the field without touching second, but only after umpire Emslie assured him that they had won the game.” (quote from Wikipedia)

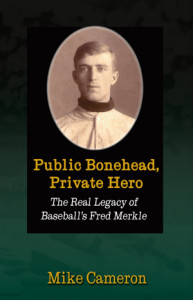

Of course, if someone had warned Fred Merkle, already considered one of the Giants’ smartest players, that Rule 59 suddenly would apply and supersede tradition for the first time in baseball history, he certainly would have trotted a few more steps and touched the bag. No one told him, so he didn’t feel the necessity to do so. The rule had never been enforced. As author Mike Cameron makes clear in his book, “Public Bonehead, Private Hero”:

”Merkle’s failure to touch second base was considered customary at the time. When National League President Harry Pulliam changed the ruling following the eerily similar ‘Gill Game,’ a mere three weeks before, he failed to immediately disseminate his decision to the ballplayers. ‘Did you have to touch second base or didn’t you?’ At the time, it just wasn’t clear. This ambiguity set the stage for the tragic chain of events of which Fred Merkle was the ultimate victim. It was a result that could easily have been avoided; Pulliam’s inaction regarding the Gill play was the equivalent of lighting a fuse to a bomb. It’s dangerous to have rules on the books which are not enforced, or to have one set of rules written down and another acted out.”

Or to change custom without telling everyone!

Legendary broadcaster Red Barber once came to Merkle’s defense: “Johnny Evers talked a great and good umpire, Hank O’Day, into making one of the worse decisions in the history of baseball. The intent in this rule [at the time] applied to infield grounders and such. It did not apply to cleanly hit drives to the outfield that make a force-out impossible unless the runner on first drops dead.” No less of an authority than Hall-of-Fame umpire Bill Klem agreed, calling it “the rottenest decision in the history of baseball. The force rule was meant to apply to infield hits, not balls hit to the outfield.” Enforcement of the rule had changed, but not everyone knew. As is well known, the game was ruled a tie. The Giants and Cubs finished the season tied for first, the Cubs won the make-up game and went on to win the 1908 World Series. And Fred Merkle lived the rest of his life with the ignominy of the “bonehead” epitaph attached to his name.

If you’re like me, you consider baseball pure fun…a sort of escapism from the trials and challenges of the “real world.” We never want to see someone’s life ruined over something that happens on the field, be it Fred Merkle, Bill Buckner, or even Steve Bartman. In spite of this handicap, Fred Merkle went on to have a solid 16-year major league career in which he hit .273 in 1,637 games, amassing 1579 hits, 82 home runs, 720 RBI, and 271 stolen bases, including 14 steals of home. As Cameron describes him:

“He was a rare power-speed player who usually hit in the clean-up spot, led four teams to pennants and contributed to two other league championships. How many people in any walk of life could endure such a handicap and still achieve success? Yet Fred Merkle did just that. He retired after baseball to a life of quiet dignity as a devoted husband, father, and successful businessman. As long as we maintain our dignity, self-respect, and strength of character, we possess the innate ability to overcome many of life’s adversities. How many of us will ever be challenged the way Fred Merkle was? And yet, somehow, Merkle managed to overcome this injustice. That is the enduring legacy of Fred Merkle’s life.’”

Well said, Mike! Here’s hoping my small part somehow helps to right a historic wrong done to a good man!

-Gary Livacari

Photo Credits: all from public domain

Information: Excerpts edited from the Fred Merkle Wikipedia page; “Public Bonehead, Private Hero,” by Mike Cameron; and “The Glory of Their Times,” by Lawrence Ritter.

Subscribe to my blog for automatic updates and Free Bonus Reports: “Memorable World Series Moments” and “Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide.”