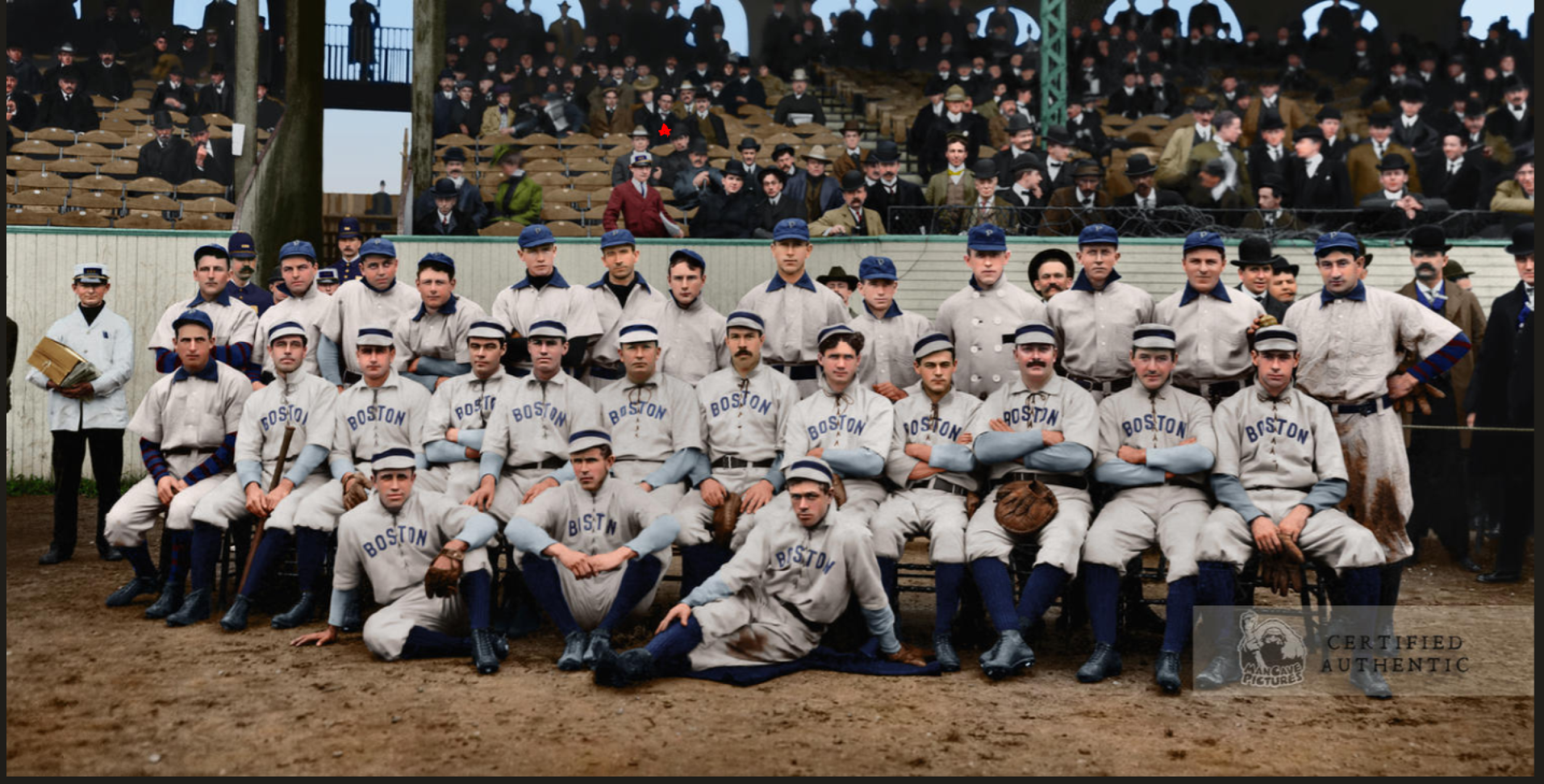

Featured Photo Above:

Combined 1903 World Series Photo: Pittsburgh Pirates and Boston Pilgrims

(Color Restoration by Chris Whitehouse of Mancave Pictures)

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

THE BASEBALL HISTORY COMES ALIVE BLOG

Please note: As we compose new blog entries, we will now send each one out to all our subscribers as we post them. Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives -GL

August 30, 2022

Black Sox Scandal Essays

Today, I’ll continue with my “deep dive’ into the Black Sox Scandal by reposting essays that first appeared in my book, Reflections on the 1919 Black Sox: Time to Take Another Look. Today I’m reposting Part Two of my three-part series on Joe Jackson. If you’ll remember, in Part One I asked the question: Did Joe Confess? Today’s essay takes a look at Joe’s play in the field and at bat. I think you’ll find it interesting.

Shoeless Joe Jackson, Part Two:

Joe’s Play in the Field And At-Bat

“You know, he was such a remarkable hitter it was almost impossible for him to swing without meeting the ball solidly.” -Teammate Dickie Kerr, speaking of Joe Jackson

Today, in another chapter in my ongoing series of essays about the 1919 World Series, I’d like to address Shoeless Joe Jackson’s play and determine how it relates to his involvement (or non-involvement) in the scandal. As is well known, he hit a Series-leading .375 with six RBIs. He hit the only home run in the Series, and played errorless ball, handling 16 chances flawlessly and throwing a runner out at the plate.

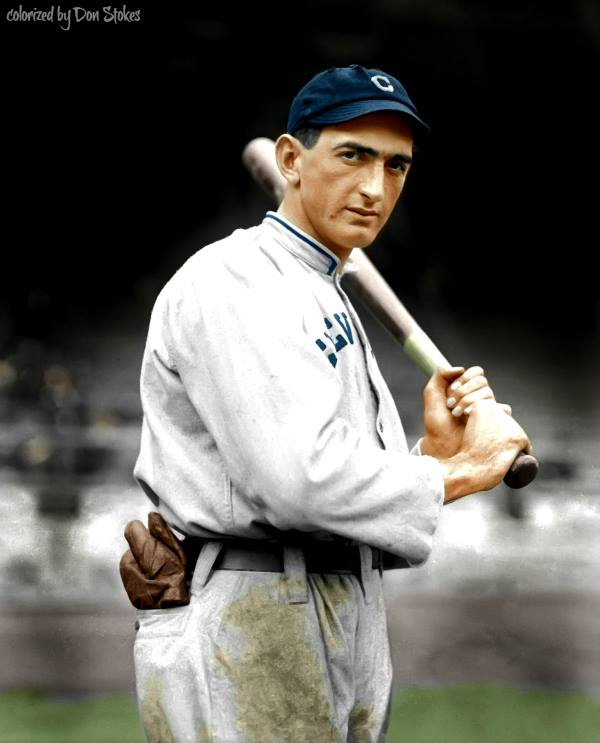

In the featured photo below, we see a beautiful colorization of Shoeless Joe Jackson by our resident baseball artist, Don Stokes.

Criticism aimed at him usually runs something like this:

“In the first five games, he came to bat with eleven men on base and never drove in a run. In the last three games, when the fix was apparently off, he drove in six runs and hit the only Series home run. He didn’t hit in the clutch in the first five games.”

If you find that criticism valid, then you have to accept the assertion that ballplayers can “pick and choose” when they want to perform well. As baseball fans, we know that just isn’t so. Many great players have had less-than-stellar World Series performances, including Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and Gil Hodges. You could easily add more to the list. The World Series by nature is a pressure cooker played in the national stoplight. Many stars have struggled, while obscure players have often inexplicably emerged as heroes. That’s just baseball.

Keeping in mind the argument Jackson “let up” in the games that were tossed (supposedly the first two games), here’s how he did in Game Two:

He went 3-for-4, with a Texas leaguer behind second that he hustled into a double; a hard single to left; and a hard smash to right that the first baseman, Jake Daubert, knocked down, then threw late to pitcher Slim Sallee, with a hustling Jackson beating the play. Does that sound like he was “laying down” in a game he knew the White Sox were trying to throw?

Let’s also take a look at the play of two other stars and see if the same argument holds up against them: Player “A” went 2-for-18 (.111) in the first five games of the Series, failing to score or drive in a single run. But in the last three games, after the fix was supposedly off, he went 5-for-13 (.385), with two runs and an RBI. Player “B” went 2-for-15 (.133) in the first five games, but 4-for-13 (.308) with three runs, two doubles, and four RBI in the last three.

If you want to hold these players to the same standards some critics hold Joe Jackson, then perhaps we should examine the play of Eddie Collins (Player “A”) and Edd Roush (Player “B”). [this idea came from baseball researcher Bill Deane in an e-mail exchange with Gene Carney]

As for his fielding, the criticism goes like this:

“Jackson was not charged with any errors in the Series, but he played out of position, he let balls fall in for hits, and three of the Reds’ triples went to left field where triples are rare.”

But in all the official accounts of the game, Jackson’s name is nowhere mentioned in any descriptions of the triples. Gene Carney asks: “Was he playing out of position, or was he playing where he should have been if the pitchers were trying for outs, and not tossing up hittable pitches?”

There’s no way to know for sure. But read this quote from Kid Gleason describing an incident in 1917 that surely would have held in 1919 when he was the manager:

“If there had been anything wrong, I would have known it. I knew everything that went on around the club.” It seems likely that Gleason would have spotted anyone playing out of position and moved them correctly. Would Gleason have just sat idly by and allowed Jackson to ‘play out of position’?”

In addition, none of the ‘Seven Suspicious Plays’ spotted by sportswriter Hugh Fullerton, who was actively looking for anything out of the ordinary, involved Joe Jackson, either in the field, on the bases, or at the plate.

I think we can put the ‘he played out of position’ notion to rest.

For that matter, other than Fullerton, none of the reporters covering the Series for the Chicago and New York papers, as well as the wire services, wrote about any plays that looked suspicious. Even reporters who were pretty sure the fix was on could not be certain. Nor did the umpires or the Official Scorer observe anything untoward. Thousands of fans watched the 1919 World Series in person and saw nothing unusual. Why? As Gene Carney writes in Burying the Black Sox:

“Because that’s the nature of baseball. Players trying their best still make errors. The best hitters can strike out in the clutch, the best pitchers can lose their effectiveness and look awful for an inning or two. If you are convinced that the ‘fix is in’ you will find suspicious plays in any ballgame. If you are not on the lookout, you will not see anything except ‘baseball’.”

In summary, Joe Jackson’s play in the World Series was, on the surface, exceptional. He hit well against a staff rated better than that of the White Sox by Christy Mathewson. He hit safely in six of the eight games, with five multi-hit games. He fanned just twice in 32 trips to the plate and fielded 16 chances flawlessly. Again, quoting from Gene Carney:

“To suggest that he intentionally hit better in certain games than in others is to suggest that he could rack up hits at will, whenever he wanted, which is ridiculous. Batters can look awful in ‘Homerun Derby,’ when the pitchers are serving up whatever the batter wants. But even accomplished hitters make outs more often than they get hits, and often the outs come in the clutch.”

Sadly, all this does not make a definite case for Joe Jackson’s honest play. It’s just one way of looking at the facts. As with all aspects of the 1919 World Series, nothing is cut-and-dry; but at least on the surface, it’s very difficult to say that Joe Jackson did not play hard the entire Series: at bat, in the field, and on the bases; and that he played every game to win, as he maintained throughout the rest of his life.

Of course, all this begs the question: If we are reasonably certain that Joe Jackson played hard and played to win the entire Series, does it really matter if he gave a contradictory statement to the grand jury, while under the influence of alcohol and after being coached by Comiskey lawyer, Alfred Austrian, and without the benefit of personal legal counsel? A statement he later refuted? If he did accept money, does it really matter if, as he always maintained, he did nothing to earn it on the field?

It was a huge mistake for him to accept tainted money, making his later protestations of innocence much harder for even his supporters to swallow; but if someone wanted to give him money, did he really have a moral obligation not to accept it as long as he didn’t let it influence his actions? He also claimed he tried to inform Comiskey about it, and tried to give the money to either Secretary Harry Grabiner or Comiskey, but was rebuffed and told to keep it. When he testified to this in the 1924 Milwaukee trial in which he sued Comiskey for back pay, 11 of the 12 jurors believed his version of events rather than Charles Comiskey’s.

Could it be, as he and others have maintained, that the gamblers and the ringleaders wanted his name associated with the “fix” so as to give an air of credibility? In that sense, was it worth it to them to have Joe compromised by giving him money? This suggestion was given credence by Lefty Williams’ testimony in the 1924 Milwaukee trial when he said under oath that he “used Jackson’s name in the meetings with the gamblers [meetings Jackson did not attend] without Jackson’s knowledge or permission.”

Jackson also claimed Williams told him “he used my name in order to wring more money out of certain fellows supposed to be gamblers.” In other words, his name and his celebrity status as a star player might have been useful to the plot whether or not he was an active participant. The gamblers could spread the word that “Jackson’s in on it”; and, as a key player, that most certainly would have affected the odds.

I think these are all questions worth further investigation when considering Joe Jackson’s role in the 1919 World Series. Again, I don’t know what really happened. I just think, after the passage of 100 years, the whole sordid mess deserves a closer look; and that the conventional wisdom does not tell us the complete story.

As far as the money is concerned, I’ll have a lot more on that in my next essay. Stay tuned…

Gary Livacari

As always, we enjoy reading your comments

Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives

Wow ! … what a riveting essay, Gary. I have been eagerly reading this series, and look forward to future entries. Please correct me if you think I am wrong, but in taking into account what historians; {and the actual participants of the ’19 Series} have stated, it could be reasonably said that Shoeless Joe was coerced into playing the role of a “patsy” in the whole scheme. Very believable if that was the intent of the perpretators. It very well could have gone down in MLB historical lore, that only SIX WSox players were actually guilty of being in on the fix; as, along with Shoeless Joe, Buck Weaver’s guilt is extremely dubious. Thnx, Gary.

Thanks Tom, glad you’re enjoying these essays. You could very well be right that he was used as a unwitting “patsy.” As I mentioned, his involvement, even if unintentional, was useful to the gamblers. Stay tuned for Part Three where I go into detail about the money.

By the way, please send me your address as I’d like to send you a copy of the book. Send it to my email: Livac2@aol.com and I’ll get it right out to you.

Excellent essays Gary. I have been interested in the “Black Sox” scandal ever since I first watched Eight Men Out as a kid. After reading your first article on this, I am now inclined to believe that this was just a massive manipulation by the gamblers. They knew Comiskey was a scrooge and the players were ripe for an opportunity to “stick it to him.” All they really needed to do was: 1. Get their bets in early on the Reds to win while Chicago was still highly favored. 2. Sweet talk the handful of necessary players and grease the skids with just enough cash to get them to know it was a serious endeavor. 3. Sit back and let their reputation of being “nobody you want to cross” burrow its way into the players psyche leading up to the first game. And as you suggested that increased pressure alone should be enough to force some on-field mistakes by the players. The gamblers then do what they ultimately did and withhold the remaining money and intimidate the players even more. Further ensuring the mental-distraction on the field and the increased chances of poor Baseball mistakes. Because really all the players are stuck between a rock and a hard place at that point. Play good and risk pissing off the “no joke” gamblers, or play bad and risk your public reputation and future livelihood as a Ballplayer? Really tough to play great with all that weight on your mind. As Swede Risberg says in the move “what are they gonna do? Call a cop?” It goes for both players and gamblers. By then the whole thing stinks and the only one’s who benefit are the crooked gamblers. I really appreciate you doing objective, truth based research and writing on this. I’m looking forward to reading more. Thank you.

Thanks a lot Kevin, greatly appreciate the kind words…I think you and I are on the same page about, as I like to call it, “this sordid affair.” And I think your summation is spot-on. I’m sure you agree with me that “there’s a whole lot more to this story than the conventional wisdom has led up to believe.” More essays to follow, please keep in touch! -Gary